Cocoa and the Death of Yellow Box and Rhapsody

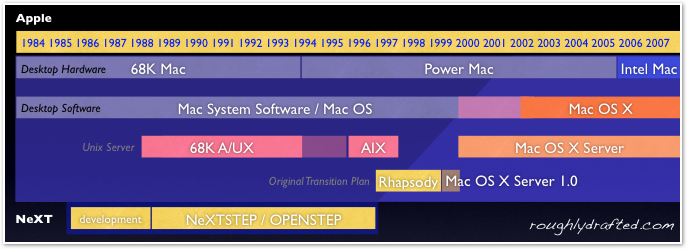

Building upon technology acquired from NeXT, Apple has leveraged open source software to make rapid progress in developing a new server business. Along the way however, Apple was forced to make major changes to its initial plans for using NeXT technology.

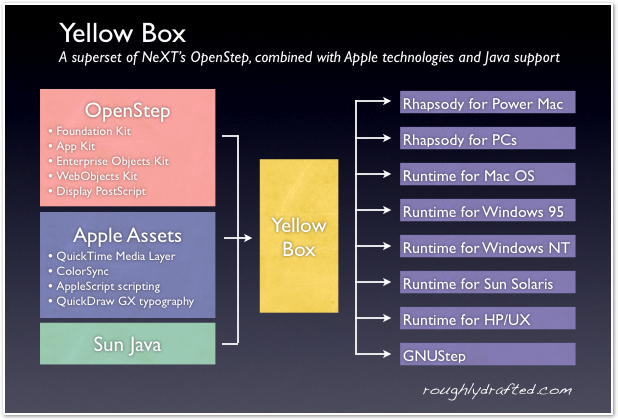

Between 1996 and 2000, the market’s rejection of OpenStep and then Yellow Box resulted in Apple significantly reworking Mac OS X to serve its own needs, rather than trying to offer a cross platform environment like Sun’s Java or Microsoft’s .NET and its open source Mono implementation. Here’s why Yellow Box as a strategy died.

Two Failures Team Up

In 1996, Apple announced the cancelation of its failed internal plans for Copland and the intention to buy an existing operating system for use in the next Mac OS. Apple briefly examined using Microsoft’s Windows NT, then began discussions with Jean Louis-Gassée to acquire the BeOS.

Apple then entered talks with NeXT, initially with the plan to license its operating system kernel. NeXT had all but given up on selling NeXTSTEP as an operating system, and had shifted its resources toward custom development:

-

•the OpenStep specification ran NeXTs development frameworks on a variety of operating systems

-

•WebObjects adapted NeXT’s development frameworks to build web applications

-

•OPENSTEP Enterprise provided OpenStep development tools for Windows NT

-

•OPENSTEP Solaris provided OpenStep development tools for the Sun Solaris operating system

-

•OPENSTEP/Mach delivered an OpenStep compliant version of NeXTSTEP for the PC, SPARC, and HP PA-RISC

NeXT was having trouble driving adoption of OpenStep however. It had an advanced operating system but no customers, while Apple had customers but no advanced operating system to sell them.

Talks between the two rapidly expanded beyond simply licensing the Mach kernel to buying NeXT and using OpenStep as a new development plan, and OPENSTEP/Mach as a new, cross platform operating system.

Rhapsody and the Yellow Box: 1997-1998

In January 1997, Apple announced plans to quickly migrate users from its existing Mac OS 7.6 to the operating system technology newly acquired from NeXT.

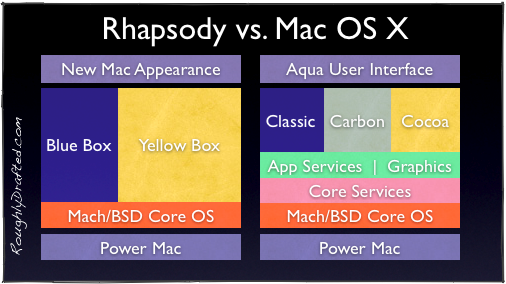

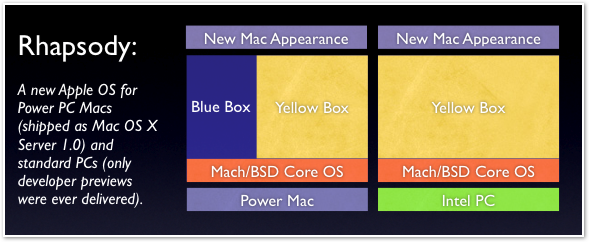

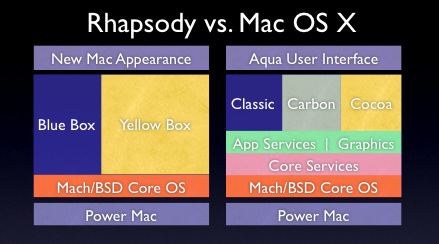

Apple’s new operating system, code named Rhapsody, would largely be based on the existing OPENSTEP/Mach 4.0, but also incorporate Apple technologies, including ColorSync and QuickTime.

It would run on both Power PC Macs and standard Intel PCs, although a Blue Box for running existing Mac apps would only ship on the Power Mac version. Rhapsody’s OpenStep environment was then labeled Yellow Box.

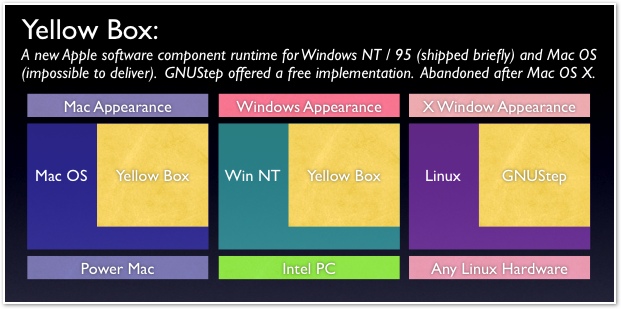

Through the magic of NeXT's highly portable OpenStep frameworks, Apple would also have a developer product to sell Windows NT/95 users. Applications written to OpenStep / Yellow Box could magically run cross platform, not just on Rhapsody, but also on Windows, Sun Solaris and anywhere else OpenStep was ported.

GNUStep, an open source version of the OpenStep specification, was also under development for Linux. Apple also briefly planned to host Yellow Box on the Mac OS, but it was quickly discarded as an unworkable option.

Under the Yellow Box plan, the world would heal from the horrific, self-inflicted wound of snubbing OpenStep the first time around, and Apple's stagnating Mac product would rebound as a modern platform, powered by NeXT. All the new software written for Yellow Box would “just work” everywhere.

Yellow Box Falls Apart

However, as work on Rhapsody continued, Apple ran into some show stopper problems:

-

•OPENSTEP included technology that turned out to be prohibitively expensive to license, including Adobe's Display PostScript.

That issue had not been problem for OPENSTEP/Mach; at the time, NeXT sold for $795 per desktop or $2790 for the full set of developer tools. However, it was a significant problem for a bundled, mass market new Mac OS and a planned, low cost Yellow Box runtime, neither of which could support expensive licensing fees. -

•More significantly, third party developers rejected the move to the Yellow Box frameworks, and demanded both a compatibility environment that could run existing Mac OS apps natively, as well as a way to continue developing code based upon the existing Mac OS APIs instead of Yellow Box.

Since the Mac OS Blue Box APIs were tied to Power PC and 68k emulation, they could not be ported to the PC version of Rhapsody and run at an acceptable speed. This helped kill the prospects of an Intel Rhapsody. -

•It was simply impossible to sell a competing product to Windows due to the Windows Price Paradox. Third party hardware makers made it clear they would not pay to offer Rhapsody as an OEM option to Windows on new PCs, due to the same Microsoft monopoly issues that hounded DR-DOS, OS/2, NeXTSTEP, BeOS, and Linux.

Cross Platform Rhapsody Falls Apart

None of those issues were critical problems holding up an Apple server product, so the company announced a new, two phased plan for its revised NeXT technology rollout:

-

•Apple would deliver Rhapsody as Mac OS X Server in 1999 for Mac hardware

-

•NeXTSTEP would be significantly reworked and follow as Mac OS X a year later

The initial Rhapsody developer previews ran on both PC and Mac hardware, but by the time it was delivered, Apple had given up on any prospects for third party licensing or cross platform support.

No PC hardware makers would agree to pay a reasonable licensing fee to bundle Mac OS X Server, and few were at all interested in doing so anyway. Apple was still increasingly being labeled as beleaguered by the press, and all attention was focused on Microsoft's upcoming new version of NT, to be called Windows 2000.

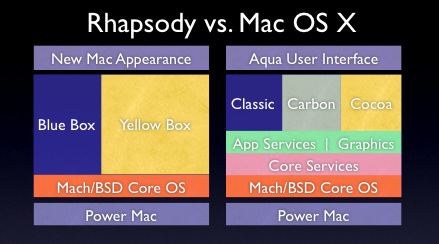

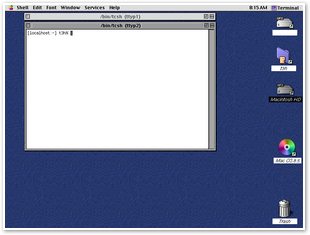

In 1999, Rhapsody shipped as a Mac-only, Power PC version of what was essentially OPENSTEP/Mach 5.0, called Mac OS X Server 1.0.

It still used Display PostScript, although it was skinned to resemble the Copland appearance of Mac OS 8.

It also included a Blue Box compatibility environment to run classic Mac applications in a virtual machine hosting a full version of Mac OS 8.

While the Blue Box consumed a lot of system resources, it actually ran most Mac apps better than a native install of Mac OS 8, because of Rhapsody’s improved OS foundation, including a better virtual memory architecture.

The new Mac OS X Server ended the life of the AppleShare IP product based upon the classic Mac OS. It also introduced NetBoot, a new way to remotely boot modern Macs from a network image. Since the iMac, Macs had been designed to boot as Network Computers, directly from a network disk image.

Mac OS X Leaves Rhapsody Behind

Two years later, Apple released Mac OS X 10.0 as the first version without Display PostScript and with a greatly reworked development architecture.

The existing classic Mac APIs were cleaned up and incorporated as Carbon, while the OpenStep derived Yellow Box was dramatically modified to become Cocoa.

The Blue Box remained as Classic, but existing Mac OS apps could be updated to run natively using Carbon, and gain access to most of the benefits of the new OS underneath.

In addition to an entirely different window server, so many other fundamental changes were made that the Yellow Box ceased to exist as a cross platform environment based upon the OpenStep specification.

Existing OpenStep applications now require a significant overhaul to run on Mac OS X, and new applications built for Mac OS X would not work on OpenStep compliant systems.

The Eternal Death of Yellow Box

After failing for NeXT as OpenStep, and again for Apple as Yellow Box, it is very unlikely that Apple will ever attempt to reintroduce the Yellow Box strategy for developing cross platform applications.

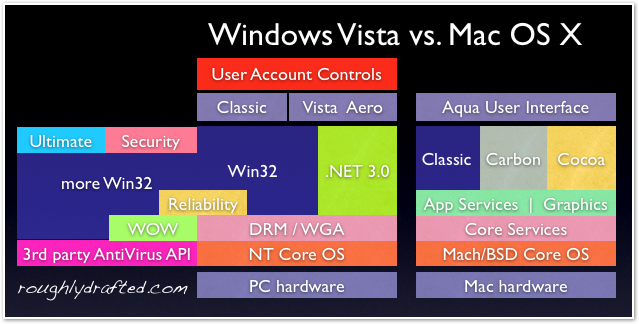

The same strategy also failed for Sun in its Java Virtual Machine, and even Microsoft has faced some difficulty in establishing .NET as its own version of a virtual machine environment. Despite clear advantages of .NET over existing Win32 legacy development, even Microsoft has been slow to move its own applications to use it.

A look at competing vendor motivations helps explain why Yellow Box is unlikely to ever rise again:

-

•NeXT originally released the OpenStep specification in order to gain adoption of its technologies. It had failed to sell its technology as an integrated product with the NeXT Computer, then failed to sell it as a third party operating system in NeXTSTEP. OpenStep was a last shot at finding users for the platform.

-

•Sun introduced Java as its own version of an OpenStep-like development environment, with the intent to own cross platform application development. The world was first excited about the prospect of cross platform development, then gave up on the JVM because it was slow and incomplete, and native solutions worked better.

-

•Microsoft introduced .NET and its CLR VM and various "#" Java-like bytecode languages to kill the threat of a Sun run Java and to instead tie Java-style development to Windows.

.NET is also Microsoft's ongoing strategy for replacing the existing Win32 development environment in Windows. Apple’s transition from the classic Mac APIs to Cocoa is comparable to Microsoft’s efforts to move from Win32 toward .NET and managed code, although Vista only offers .NET as an option.

Similar to Apple’s troubles with Rhapsody, Microsoft intended to move its developers to WinFX in Longhorn, then scuttled the plans after developers insisted they wanted to stick with old things they already knew.

Apple Runs With Cocoa

After repeatedly finding the market unappreciative, Apple is no longer interested in offering tools to develop cross platform applications. Apple now lacks both the motive and the opportunity.

Apple wants to deliver software that sells Mac hardware, not own cross platform development in a Java or .NET manner. Further, the support behind .NET would make a new Yellow Box strategy very difficult to pull off in a market more crowded than it was a decade ago.

Further, after fruitlessly chasing Java support for years, Apple has dropped any intention to run after the taillights of Java or .NET, and is highly unlikely to get behind efforts like Mono.

Instead, Apple has focused its efforts on using its own technologies itself, rather than trying to tempt others into using them. Key technologies from NeXT, including Cocoa and WebObjects--basically Cocoa for the web--have been used by Apple to deliver:

-

•the online Apple Stores for education, businesses, and various regions

-

•the iTunes Stores for various regions and iTunes U for education

-

•applications bundled with Mac OS X and in its iLife and Pro App suites

-

•Apple is also adapting Cocoa technology to power the iPhone.

These examples all demonstrate that Apple is not trying to increase its dependance on third parties or plead with them to develop using its tools. Instead, Apple is using its tech portfolio to build its own products.

Despite the company's striking success in rapid application development, powered by its now free development tools, outside developers have been slow to make much use of them. If Apple had held its breath waiting for third parties to adopt its technologies, it would have passed out long ago.

Focusing on fully exploiting the value of its own technology leaves Apple ahead of the game in offering unique and distinguished products because using its own tools, it can develop new products faster than its rivals.

While Cocoa helps to rapidly develop front end interfaces to applications, Apple also leverages the power of open source to build the engine underneath. The next article outlines how the combination of Cocoa and open source have been used to rapidly deploy a new line of server products: Open Source in Apple’s Server Efforts

Next Articles:

This Series

|

|

|

|

Del.icio.us |

Del.icio.us |

Technorati |

About RDM :

:

Technorati |

About RDM :

:

Monday, February 19, 2007

Send Link

Send Link Reddit

Reddit NewsTrust

NewsTrust