The Egregious Incompetence of Palm

Windows Mobile, Palm OS, Linux, and Symbian currently power the world’s smartphones. How does each stack up against Apple’s OS X in the iPhone? This article presents an overview of Palm.

Palm's early products actually followed a trajectory strikingly similar to Apple's original Macintosh. Differences in the choices made at Palm provide an interesting glimpse into "what if" scenarios of a parallel universe.

Here's a look at the decisions that shaped the destiny of the Palm dynasty, and why Palm fell from its position as a dotcom-era darling enjoying a golden age of prosperity to become a modern day CP/M, well past its prime.

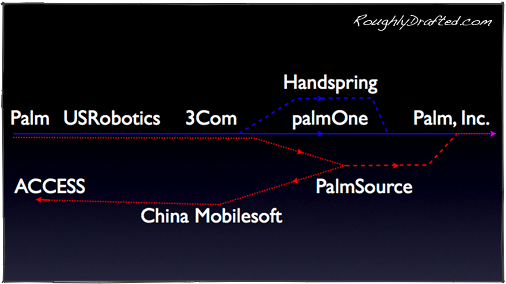

The identity of Palm and its OS have changed dramatically over the last decade under the stewardship of various different groups and companies. Palm has been bought up, passed from one company to the next, spun off, split, merged, and regrouped, and the Palm OS has been licensed to independent developers.

In contrast, WinCE has maintained a steady history within Microsoft under the same management over the last decade, as was previously detailed in The Spectacular Failure of WinCE and Windows Mobile.

Palm's Unfulfilled Potential

Palm suggested a lot of tantalizing potential that was never really delivered. Phone integration features in its latest Treo line are frustratingly just minimally sufficient.

The potential of third party apps on the Palm has largely been neutered by Palm's incompetent handling of the Palm OS, limitations in hardware, and sync functionality that only works well on lucky days of the week.

These flaws complicate each other: the bare bones amount of Flash and system RAM available complicates sync features and app installation, because once the memory ceiling is reached, a Palm device refuses to sync. The user has to manually delete cryptically named applications and databases from the device to make enough room. Stability is another problem related to both OS development issues and hardware limitations.

In many ways, the Palm OS has hit the wall in a manner similar to Apple's Mac System 7 in the early 90s. Problems in the Palm OS relate to legacy issues from the late 90s, just as Apple's problems with the Mac were bound to design considerations made a decade prior. Just as the Classic Mac's golden age was in the late 80s and early 90s, Palm's occurred in the late 90s and into the millennium.

The Golden Age of Palm: 1996-2002

The Golden Age of Palm: 1996-2002Jeff Hawkins, the visionary behind the original Palm Pilot, had earlier pioneered ideas in pen computing at GRiD. His first attempt to design a PDA for the consumer market, the Casio Zoomer, was a huge failure, selling only a tenth as well as the Newton.

After the disappointing failure of the Zoomer, Hawkins founded Palm Computing to develop third party software for other manufacturers' handheld devices, including the Graffiti simplified text input system for Newton.

Hawkins also started work on a reference platform for a new PDA, aimed at the low end of the market and capitalizing on a simple subset of practical features for consumers: the Palm Pilot.

Hawkins shopped the idea around to find another Casio interested in making a cheaper alternative to Apple's excessively sophisticated Newton. Modem manufacturer US Robotics agreed to buy Palm in 1995 for $44 million and enter the PDA business.

Palm Pilots ended up outselling both the Newton--which Apple canceled just as the Palm started really taking off--and Microsoft's WinCE devices, which weren't even remotely competitive with the much simpler and practical Palm OS devices until around 2002.

Rather than attempting to offer state of the art hardware and development concepts, the Palm Pilot was designed to do simple tasks well on low cost hardware.

That resulted in a good, popular product in throughout the late 90s, and allowed Palm to experience a golden age of nearly uncontested development during its first several generations of Palm PDAs.

Luckily for Palm, this period also corresponded with a huge bubble of tech spending, giving the nerdy gadget a perfect window of opportunity to become both popular and profitable.

Soul of a New Palm: 1995-1997

To build the new Pilot PDA, Palm Computing chose the DragonBall, an embedded version of Motorola's popular 68k processor that powered the original Macintosh, Amiga, Atari ST, and the Sega Genesis.

Palm's simple OS was designed on top of a multitasking kernel licensed from Kadak, although Palm's license did not allow support for its multitasking features.

A number of factors combined to make the Palm Pilot resemble Apple's original Macintosh design:

-

•it used a highly integrated, customized hardware design based on the 68k processor

-

•it used a simple, practical monochrome display rather than trying to do color poorly

-

•it lacked sophisticated operating system features, and focused instead on usability

-

•it was designed to be a practical tool, not just impress geeks with raw, unusable tech potential.

US Robotics introduced the first generation Palm Pilot 1000 and 5000 in March 1996 for $300 and $400, and followed up with the enhanced Palm Pilot Personal and Professional versions a year later.

Two months afterward, US Robotics was bought up by 3Com in June 1997. Palm's founders had hoped to adapt the platform into new markets, but 3Com had more conservative plans for its third generation Palm III, set for release in 1998.

Within a year, Hawkins, Donna Dubinsky, Ed Colligan and others from the core Palm team left 3Com to form Handspring, intending to develop their own vision of the future of Palm.

Newton Supernova: 1997-1998

Prior to 1997, Apple's Newton MessagePad line hadn't seen any earth shattering updates since its debut in 1993. However in March 1997, Apple introduced a new line of significantly faster and improved models, including the MessagePad 2000 and the eMate 300, a tiny Newton OS laptop designed for education markets.

That move suggested Apple was suddenly getting serious about the handheld market, after three years of unclear prospects of Newton’s future outlook.

The new models were announced just three months after Apple bought NeXT; two months later, Apple CEO Gil Amelio announced that Newton would be spun off as an independent company, called Newton, Inc.

Newton, Inc. w as created on July 2, 1997. A week later, Amelio was ousted by Apple’s board of directors, and Steve Jobs was named Apple's interim CEO. On September 19, Jobs pulled Newton back into Apple.

as created on July 2, 1997. A week later, Amelio was ousted by Apple’s board of directors, and Steve Jobs was named Apple's interim CEO. On September 19, Jobs pulled Newton back into Apple.

as created on July 2, 1997. A week later, Amelio was ousted by Apple’s board of directors, and Steve Jobs was named Apple's interim CEO. On September 19, Jobs pulled Newton back into Apple.

as created on July 2, 1997. A week later, Amelio was ousted by Apple’s board of directors, and Steve Jobs was named Apple's interim CEO. On September 19, Jobs pulled Newton back into Apple. In a private email about the move, Jobs reportedly wrote, "The Emate has a bright future," and "sales of the current MessagePad are brisk."

"Don't worry, we are pulling this group back into Apple so that we can invest even more sales and marketing resources into these products, rather than dumping the products into a small spin-off which lacks such resources."

"Don't worry, we are pulling this group back into Apple so that we can invest even more sales and marketing resources into these products, rather than dumping the products into a small spin-off which lacks such resources."

The next month, Apple released the Newton MessagePad 2100, alongside a new, simplified lineup of G3 PowerBooks and PowerMacs, and a new online web store.

Apple also announced a net loss of $1 billion for fiscal 1997, although that included $667 million in expenses related to buying NeXT. Apple had lost $816 million the previous year under Amelio.

The cheapest Newton eMate was $800, and the MessagePad was over $1000. Palm Pilots were $300-400; that huge price difference, along with the Palm's much smaller and more practical pocket-size format, made the conservative Palm Pilot popular and killed any hopes for a mass market Newton resurgence.

IDC reported that Apple only sold 60,000 MessagePads in 1996, down from 100,000 units in its first year. Palm sold a million PDAs in its first year and a half, and Palm sales were booming.

Intel had also just taken over DEC’s processor business, including the StrongARM processor used in the MessagePads. Uncertainty about Intel’s interest in continuing StrongARM development, flagging unit sales, and attempts to simplify its product lineup all contributed to Apple canceling Newton development in February 1998.

Hawkins' NeXT - Handspring: 1998-1999

A few months after the official death of Newton was announced, Palm's founders left 3Com to form Handspring and start work on a new Palm PDA called the Visor.

Handspring licensed the Palm OS from 3Com and began building nearly identical devices which were compatible with existing Palm software but offered some key enhancements.

Handspring released its new Visor in September 1999, a year after Apple launched of the iMac. Capitalizing on the popularity of Apple's new consumer system, Handspring included built-in support for USB and the Mac OS with the Visor. Earlier Palm Pilots had required an extra serial to USB connection kit in order to work with Macs.

The Visor also provided a Springboard expansion port that could transform the unit into a camera, a music player, and eventually a mobile phone.

Palm Cuts Wires, Strings: 1998-1999

While Handspring's devices were marketed toward consumers, 3Com aimed its own Palm development toward business customers. Rather than turning the Palm into a mobile phone, 3Com planned to offer a wireless Internet device aimed at professionals.

The wireless Palm VII used Mobitex, a first generation wireless data network also used by two way pagers and the first BlackBerry devices. The device intended to allow users to access simplified versions of web pages, called web clippings. The service turned out to be too expensive and slow to be very practical however.

Apart from the Palm VII, 3Com's other Palm products remained basic organizers. The pinnacle of its basic PDAs was the Palm V line, introduced in October 1999, which had an ultra-slim case and exceptional battery life. Oddly, there were no even numbered Palm II, IV, or VI models.

IBM resold various Palm models under its own Workpad brand. 3Com also began licensing the Palm OS to other vendors, including Symbol Technologies for use in its handheld barcode scanners, and Qualcomm Wireless in its line of mobile phones with an integrated Palm PDA, called the pdQ.

Qualcomm later sold off its phone hardware business to Kyocera. Sony, Nokia, and Motorola, among several others, also signed up to license the Palm OS in their own devices. Fossil even designed a miniature Palm OS watch.

Palm Supernova: 2000

Two years after the death of the Newton, Palm hysteria had grown into an insane frenzy. Palm sales were surging, and the Palm OS was seen as the next Windows for handheld devices.

Liberal spending during the dotcom bubble had inflated an unsustainable demand for tech toys. That meant that, unlike a lot of startups at the time, Palm was actually turning a profit.

In late 1999, 3Com announced plans to spin Palm off into an independent company. It really wanted to get out of PDAs before the market realized what was about to happen. Insiders knew the Palm OS was losing steam as an aging platform, and that mobile phones with organizer features would eventually obsolesce the standalone PDA.

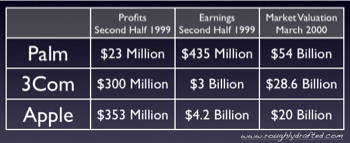

After announcing the Palm IPO, 3Com’s shares rose by 400%, despite the fact that Palm devices only accounted for a tenth of its sales. As depicted in the chart below, in the second half of 1999, 3Com's Palm division had made $23 million on sales of $435 million; 3Com had earned ten times as much: $300 million, on $3 billion in sales. In comparison, Apple had earned $353 million on sales of $4.2 billion.

The market went nuts for Palm: it was new, abuzz, and its familiar devices were showing up everywhere. 3Com planned to offer 5% ownership of Palm at around $15 a share to raise $330 million, but then more than doubled the initial share price to $38. The market didn't even flinch.

Palm shares rocketed to $140 before settling around $95. Palm's IPO actually earned $874 million.

At $95, the market had valued Palm at $54 billion, compared to the far more profitable 3Com at $28.6 billion and Apple's market cap of $20 billion.

Within a month, Palm shares had dropped back below its IPO price. The overall market was convulsing, and PDA sales in particular were about to take a dive.

The Death of the PDA: 2001-2002

Excitement about Palm caught the attention of Microsoft. After years of struggling to copy the Newton with Handheld PCs running WinCE, the company was blindsided by Apple's withdrawal from the market in 1998.

Microsoft then scrambled to changed course and copy Palm's success with its Palm PC reference designs. That product was so badly received that Microsoft had to rename its WinCE PDAs as Pocket PC in 2000.

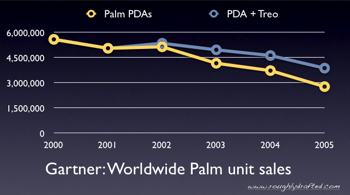

As easy money dried up in 2001, the market began to demand more practicality. PDAs were an easy casualty. Palm unit sales dropped 10%, from 5.5 million in 2000 to 5 million in 2001.

Handspring remained ahead of the curve by introducing a $300 expansion cartridge called the VisorPhone that turned its Visor PDA into a GSM mobile phone, a forerunner to the Treo.

Handsprings’ unit sales grew more than 20% in the same period, from 1.3 to 1.6 million in 2001.

In 2000, the Palm OS powered 86% of PDAs. Over the next several years, WinCE based Pocket PC devices steadily absorbed an increasing share of the market, but there was little growth in PDAs.

The yellow line above tracks Gartner’s worldwide PDA sales, which exclude the Treo. Palm acquired the Treo line when it merged with Handspring in 2003. To be fair, I added Treo sales into the blue line. It didn’t help much.

WinCE promised to support a larger range of hardware and offer access to far more memory and processing power than the Palm OS was ever designed to accommodate. Fortunately for Palm, Microsoft couldn't quite manage to deliver on its promises over the next several years. Unfortunately for Palm users, Palm did little to capitalize on Microsoft's sloth and incompetence, and instead made too many blunders of its own.

Palm Copies Apple: 2002-2003

Palm found itself in a position similar to Apple in the early 90s: falling behind while watching its once glorious empire slowly fall to Microsoft licensees. It made a number of efforts remarkably similar to Apple's.

Copland: Rather than rapidly pushing the Palm OS to a new foundation with modern OS features, Palm struggled with the Palm OS much like the old Apple struggled with its aging Mac System Software between 1991 and 1997.

Efforts to deliver a fully modernized Palm OS similarly never materialized at Palm between 2001 and 2007 either.

Move to RISC: Instead, Palm moved the Palm OS from DragonBall processors to the more modern ARM Architecture in 2002; this step mirrored Apple's move from 68k to PowerPC.

Incidentally, as a major investor in ARM, Apple had been padding its profits since 1998 by selling off its shares in the company, earning back at least $792 million on its Newton adventures.

Palm was left with an old OS running on a fast new processor. However, unlike Apple's 1994 move to PowerPC, Palm developers weren’t actually able to use the full power of the new ARM based Palms. Essentially, Palm had moved the old Palm environment to new hardware without much actual benefit for users.

Even worse, Palm's transition wasn't as smooth as Apple's move to PowerPC Macs. The new Palm OS 5 ran on faster processors and allowed for more memory, but many older applications were incompatible with the new OS and the new Palm devices that required it.

Product Simplification: Palm also decided to greatly simplify the number of models it was trying to sell. A wide swath of numbered models were replaced by the Zire consumer brand and Tungsten prosumer brand.

DIY Hardware Focus: Just as Apple ended cloning by buying out Power Computing--its most successful cloner--and refocusing its hardware efforts, Palm bought up Handspring in 2003 to capitalize on its Treo mobile phone.

Bring Back a Founder: Palm's purchase of Handspring was also a bit like Apple's purchase of NeXT: it brought back a founder with a passionate vision for new products to replace the soulless management killing innovation.

That's also where the similarity between Apple and Palm end. While Apple obtained an entirely new OS from NeXT and used the technology to build itself a new foundation for future Macs in Mac OS X, Palm implemented a series of increasingly ineffectual blunders.

It may have been wiser for Palm to continue copying Apple, and obtain a second wind of software technology by licensing Psion's EPOC, which later became known as the Symbian OS.

Palm Follows Pundit's Advice for Apple: 2003-2007

Remember when pundits all insisted they knew exactly how to fix Apple? Apple mostly ignored their advice, which ended up being fortunate for today's Mac users.

Palm's history of following all that advice--and paying the severe consequences--provides an interesting view into an alternate universe of possibility: what might have happened to Apple had it been run by John Dvorak, Paul Thurrott, Rob Enderle, and a gaggle of other columnists with conflicting opinions on how to save it.

They incessantly insisted that Apple desperately needed to:

-

•License its OS to other hardware makers

-

•Copy Microsoft's Windows strategies

-

•Compete directly against Microsoft in IT markets

-

•Split into hardware and software companies

-

•Buy Be, Inc. for its BeOS

-

•Adopt the Linux kernel

-

•License Windows from Microsoft

While Apple ignored all their free advice, Palm jumped in and followed it to the letter. The result: Palm is on extended life support and peddling a device that will be completely obsolete in six months.

License the OS to other hardware makers. Palm made efforts to license the Palm OS to other manufacturers from the start. The benefit to Palm was questionable; it made its real money selling hardware, just like Apple. After four years of pumping out Palm OS based Clié models, Sony backed out in 2004.

Other makers' efforts to build Palm PDAs were modest; mobile phone makers apart from Handspring didn't make much of an impact either. The only reason why Palm is still around is because it gobbled up Handspring and gained a product it could sell: the Treo line of Palm-based mobile phones.

Copying Microsoft's Windows Strategies sounds like a good idea when the wags repeat it, but the problem with copying Microsoft is that it never works for anyone who isn't already in Microsoft's position. Without significant and largely unchallenged dominance of an industry, other companies can't use Microsoft's tricks, which involve tying products together in integrated ways to become a one stop shop for customers.

Apple has found success in markets by blazing its own trail, and has ended up in a powerful position in music and movie downloads, music players, applications, and integrated hardware.

Apple has become a Microsoft of sorts by following non-Microsoft tactics. As a result, the company is now in a position to begin copying Microsoft's integration. Just a few years ago, however, Apple didn't dominate anything, making efforts to emulate Microsoft impossible.

Similarly, by 2004 Palm was tied in market share with WinCE in the stagnant PDA market. There was no success to copy, because there was no IBM offering a free ride, and nobody wanted PDAs anyway.

Compete directly against Microsoft in IT markets. Efforts to push corporate sales of PDAs didn't really work out for Palm. The real growth in PDAs was lead by Handspring's consumer focus and push into mobiles. Microsoft found this itself as it pushed WinCE at unappreciative business users. There was no lucky break waiting for PDAs as there had been with the PC in the early 90s.

Split into hardware and software companies. Pundits liked to say that if Apple spun off its hardware division, it could sell both Macs and Windows PCs, and that its OS should be an independent company selling software for both Apple’s Macs and other makers’ PCs. It sounds like such a great idea. It didn't work out for Palm, though.

In 2002, Palm created a subsidiary to develop the Palm OS, and later spun it off as PalmSource. The hardware remains of Palm merged with Handspring the next year to create palmOne. This was confusing for people who thought they owned a Palm, when really they had bought a palmOne device running Palm OS from PalmSource.

PalmSource released plans to ship a successor to Palm 5 Garnet (think: the PowerPC version of Mac OS 7) as Palm 6 Cobalt (think: the mythical, PowerPC-native Copland). Hardware licensees were not interested in the new Cobalt, which promised to provide native support for the ARM processors in the the latest Palm devices. Not even palmOne began using PalmSource’s new Cobalt OS.

Buy Be, Inc. for its BeOS. In 2001, long after Be had proven it had little left to offer, Palm paid $11 million for the BeOS that Apple had passed on back in 1996. The only remaining value at Be was the ability to sue Microsoft for destroying its business, which ended up being worth a $23 million settlement.

Palm poured the development resources it obtained from Be into developing the Palm OS 6 Cobalt that nobody wanted. Key talent from Be, including Steve Sakoman and Dominic Giampaolo, ended up at Apple. Sakoman had originally started the Newton team at Apple prior to leaving for Be; Giampaolo was one of the brains behind Be's rich metadata searching, and subsequently a key architect of Mac OS X's Spotlight technology.

Adopt the Linux kernel. After frittering away the remains of Be, PalmSource bought up China Mobilesoft in 2004 and announced that future versions of the Palm OS would run on top of the Linux kernel, in addition to ongoing development of the existing custom Palm kernels used in Garnet and Cobalt.

The next year, PalmSource changed plans again, saying that development of both Garnet and Cobalt was over, and that all new development would be moving to Linux. Shortly afterward, PalmSource was bought up by ACCESS, a Japanese embedded developer.

The remains of palmOne licensed the remains of Garnet from ACCESS, and renamed itself Palm, Inc.

ACCESS, meanwhile, has rid itself of the Palm name, and now plans to call Palm OS 5 simply Garnet. The new “Palm OS” based upon Linux is now called the ACCESS Linux Platform; it has no real relation to Palm.

License Windows from Microsoft. Meanwhile, the hardware side of Palm, now simply Palm, decided to begin licensing Windows Mobile for use on its Treo hardware.

License Windows from Microsoft. Meanwhile, the hardware side of Palm, now simply Palm, decided to begin licensing Windows Mobile for use on its Treo hardware. In order to support Windows Mobile, Palm had to reduce the Treo's screen screen resolution from 320x320 to 240x240.

The WinCE version also provides multitasking support, so when users switch focus between apps, other apps continue to run in the background eating up processor cycles. This makes Windows Mobile feel a lot slower than the Palm version of the same phone.

Palm's licensing of Windows Mobile not only casts doubt upon its own plans for the Palm OS--it owns perpetual development rights to Garnet--but saddles the company with outside technology dependent upon the whims of Microsoft, and ensures that there is little differentiation between its products and those of other Windows Mobile licensees.

Inedible Dog Food

Palm’s inability to stomach its own Palm OS is a bad sign, but its move to Windows Mobile is even more disturbing because even Microsoft is avoiding use of WinCE in the products it builds.

Sony and other licensees have also given up on the Palm OS. During the four years that Sony licensed the Palm OS for its Clié PDAs, Sony’s partnership with Ericsson was also working with the Symbian OS, an embedded system that currently powers the majority of mobile phones. How does Symbian compare to Apple’s OS X?

The next article will take a look. Origins: Why the iPhone is ARM, and isn't Symbian

Next Articles:

This Series

|

|

|

|

Del.icio.us |

Del.icio.us |

Technorati |

About RDM :

:

Technorati |

About RDM :

:

Wednesday, January 31, 2007

Send Link

Send Link Reddit

Reddit NewsTrust

NewsTrust