One of the surprises unveiled in the WWDC keynote was the beta release of Safari 3.0 for both Mac OS X Tiger and Windows XP and Vista. While it was known that a new version of Safari would appear in Mac OS X Leopard in October, getting a beta now for today’s Tiger was news.

The release of Safari for Windows PCs went even further, raising the question of why Apple would port its browser to a platform that perhaps has too many already:

-

•Microsoft's own, tightly bundled Internet Explorer

-

•Mozilla's Firefox

-

•its commercial sibling Netscape, offered by AOL

-

•many other alternatives including Opera.

Here’s a look at Apple’s involvement in the history of the web browser market, with a particular focus on why Apple would choose to develop a free browser for Windows when there are already so many options available.

Why Were Web Wars Waged?

A related but commonly unasked question is: why has web browser software--a fairly simple and mundane concept in the tech world--been at the center of one of the largest and most well known vendor wars?

The short answer, of course, is that the simple web browser is really a critically important key that unlocks a phenomenal amount of power in both consumer and Enterprise markets.

A historical overview of the web browser helps to explain why, and offers further illumination into the subject of why Apple delivered its own Safari browser for Windows. Here’s an introduction to the origins of today’s web.

Blazing The Hyperlinked Trail: 1987 - 1996.

Prior to the first unveiling of its Safari browser in 2003, Apple largely depended upon third parties to deliver the Mac’s web browser. However, sixteen years before the arrival of Safari--and several years before the development of the web as an Internet service--Apple itself released the first mainstream application for developing and using hyperlinked text and media: 1987's HyperCard for the Macintosh.

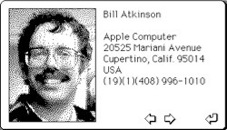

Just like Safari, HyperCard was offered for free. Apple’s Bill Atkinson, who had worked on HyperCard since 1985, assigned the rights to Apple under the condition that the company would bundle it for free on all new Macs.

That made HyperCard more popular with Mac users than Apple’s executives, who ended up marginalizing its continued development until it eventually fell into obsolescence.

HyperCard was spun off into the Claris software subsidiary where it was left to rot. It was later merged into QuickTime as a planned scripted interactivity layer called QuickTime Interactive, but was never actually delivered.

The remains of HyperCard as a product were eventually abandoned, along with QTi, during Steve Jobs’ housecleaning purge that followed Apple's acquisition of NeXT in 1996.

Inspired by HyperCard.

The legacy of HyperCard lived on however. Apple turned its HyperTalk scripting language into the Mac’s system wide AppleScript architecture for building scriptable actions, complete workflows in the recently released Automator, or even full blown apps using AppleScript Studio, now a part of Mac OS X’s Xcode.

HyperCard also helped inspire a series of projects to deliver visual application development, hyperlinked media, and scripted presentation environments, including:

-

•NeXT’s 1988 Interface Builder for graphical, rapid application development.

-

•Microsoft’s 1991 Visual Basic development environment.

-

•Netscape’s 1995 JavaScript for the web.

-

•Macromedia’s Director Lingo script and Flash ActionScript.

HyperCard also helped to ignite the development of the web itself, both directly and indirectly.

The Tangled Web We Wove: 1990 - 1992.

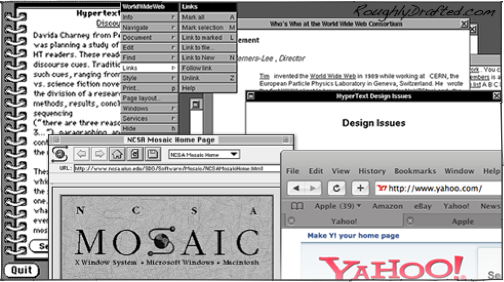

The world’s first web browser, called WorldWideWeb, appeared in 1990. It served as the client software for a new www Internet service, which defined HTTP, the HyperText Transmission Protocol, as a way to deliver linked hypertext documents from www servers hosting pages to the www browsers requesting them by URL addresses.

The web was developed by Tim Berners-Lee using NeXTSTEP, the development tools, frameworks, and operating system of Steve Jobs’ NeXT Computer. NeXTSTEP later became the basis for Apple’s Mac OS X.

NeXT was central to the development of the the web largely because it offered uniquely advanced rapid development tools, but also because NeXT occupied a niche in higher education and provided full support for the open Internet at a time when few consumer PCs did.

By using advanced technology to apply open standards, the web resulted in a system that was open to further contributions from other developers, resulting in rapid advances in utility and sophistication.

Add HyperCard and Voila: Viola.

At the same time, Pei-Yuan Wei at UC Berkeley began work on Viola, a project to bring the features of HyperCard to Unix terminals running X Window. “I got a HyperCard manual and looked at it and just basically took the concepts and implemented them in [X Window for Unix],” Wei later explained.

Wei intended to adapt Viola to use the Internet to distribute its hypermedia documents, but then happened upon the work already done by Berners-Lee on NeXT.

Adopting the HTTP architecture of Berners-Lee’s www service resulted in the creation of the ViolaWWW web browser for X Window systems in 1992. The web was weaving.

Consumer Online Systems Before the Web: 1985 - 1995.

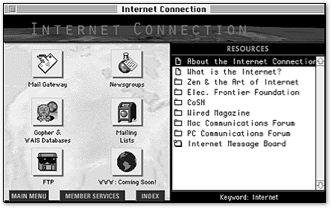

Access to the Internet remained largely confined to academia and government users until the mid 90s. In the consumer space, a series of online services, including The Source, CompuServe, Prodigy, GEnie, and Quantum, offered dial-up users access to a range of information services.

These text-based services offered gaming, forum, and email messaging all built using non-interoperable, proprietary technologies. That made it impossible to communicate with users on other systems and limited the amount of content each company could develop and offer. It was also difficult or impossible for third parties--and particularly small players--to contribute much to these systems.

In 1985, Apple partnered with GE to develop the Macintosh-based AppleLink online service for its dealer network. It used an innovative graphical client similar to the Mac Finder, but GE’s network was prohibitively expensive.

Apple partnered with Quantum between 1987 and 1989 to deliver a more cost effective consumer service called AppleLink, Personal Edition. It gave home users access to an affordable, fully graphical online system that competed against the text based services then commonly in place. Apple later pulled out of the partnership and Quantum renamed the service America OnLine.

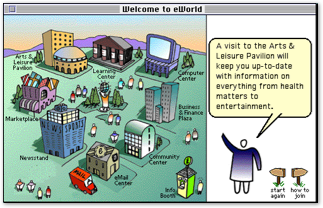

In 1992, Apple returned to work with AOL on developing an Apple-centric version of the AOL service called eWorld, which was introduced in 1994. Meanwhile, in conjunction with the release of Windows 95, Microsoft belatedly began its own graphical online service modeled after AOL called MSN.

Open Standards Kill the Proprietary Star: 1993 - 1995.

While all of these proprietary systems were working to establish themselves as rival services, consumers began demanding interoperability. Commercial access to the Internet got started as these various services began opening email Internet gateways, allowing email sent by GEnie users to relay over the Internet to AOL users. Once started, this open access began tearing down any reason for proprietary online systems to exist.

Service providers scrambled to reinvent themselves as Internet Service Providers of open access to the entire Internet, rather than closed fiefdoms offering paid access to just their own unique content.

What really destroyed any remaining hope for AOL, eWorld, MSN, and the other proprietary online services was the arrival of an Internet web browser for consumer PCs.

Al Gore Funds Development of the Open Internet: 1991 - 1993.

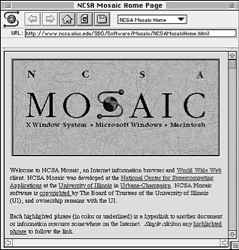

Authored and advocated by US Senator Al Gore, the High Performance Computing and Communication Act of 1991 funded the development of the National Center for Supercomputing Applications’ High-Performance Computing and Communications Initiative, which included development of the Mosaic web browser.

NCSA’s Mosaic browser could be downloaded for non-commercial use and was rapidly made available to consumer operating systems, including the Amiga, the Mac, and Windows.

While modeled after earlier browsers, including ViolaWWW, Mosaic’s support for popular computing platforms, its ability to view graphics inline within web pages, and its focus on being easy to use for non-technical users all worked to rapidly make it the most popular web browser.

While still painfully slow over existing dial-up networks, the www service presented by the Mosaic browser offered the tantalizing potential for replacing canned content systems modeled after AOL.

The web was a wide open network that could be contributed to by anyone with the ability to edit HTML documents and offer them up on a web server.

All You Need Is War.

Blossoming availability of Internet access paired with a wide open playing field of standards-based, interoperable technology resulted in both rapid innovation in the development of browser client software as well as a bumper crop of new information access as individuals and companies scrambled to publish their content for web visitors.

The only thing missing was territorial warfare, market uncertainty, and a resulting technological famine. Human nature did not fail to disappoint! Coming up next: Web Browser Wars: Netscape vs Internet Explorer.

Like reading RoughlyDrafted? Share articles with your friends, link from your blog, and subscribe to my podcast!

Did I miss any details?

Haloscan Q107

Bookmark on Del.icio.us |

Bookmark on Del.icio.us |  Discuss on Reddit |

Discuss on Reddit |

Critically review on NewsTrust

Critically review on NewsTrust

Forward to Friends |

Forward to Friends |

Get RSS Feed |

Get RSS Feed |

Download RSS Widget

Download RSS Widget

Check out the Daily Show Multi-Pass on iTunes.com

Next Articles:

Does Leopard Look Like Vista?

BHOze and the BHOzing BHOzers that BHOze Them.

EA’s Intel Mac Games: WINE and Cheese??

This Series

Safari on Windows? Apple and the Origins of the Web

Monday, June 18, 2007

Ad