After twenty years of struggling to contend with the emergence of television, movie studios began to realize that the only way to survive would be to adapt to changes in demand.

MCA’s new Laserdisc hoped to bring high quality movies into the home, as soon as the bugs could be fixed. In the meantime, the new VCRs hoped to do the same, while additionally allowing users to both record TV shows and film home movies using a video camera.

Studios were cautiously optimistic about a new videodisc, but adamantly opposed to video tape recorders and the imagined crimes they could be used to commit.

Beyond the studios’ paranoia, there were two other barriers that greatly slowed the progress of home theater.

The first was a brutal series of format wars that wasted tremendous resources and created uncertainty in the market. Like all wars and other sources of uncertainty, these format conflicts upset the market and stalled the advance of technology.

It wasn’t until these format wars--and overall studio opposition--were resolved in the mid 80s that the rapid pace of technical advancement in home theater could begin.

The Fragile Market: Standardization by Decree vs. Competition.

During World War II, the FCC set up the National Television Standards Committee to develop an American TV standard, based upon the recommendations and input from a variety of radio manufacturers.

Standards for NTSC color TV were similarly developed by consensus in the 50s. A rival, incompatible color system developed by CBS was pulled off the market by the government to prevent competition from splintering the nascent TV industry and creating confusion and frustrating incompatibility problems for consumers.

Standards for NTSC color TV were similarly developed by consensus in the 50s. A rival, incompatible color system developed by CBS was pulled off the market by the government to prevent competition from splintering the nascent TV industry and creating confusion and frustrating incompatibility problems for consumers.As the pace of technology increased, this style of consensus decree in setting standards was called into question by companies that wanted more freedom to innovate. While the FCC continued to rule certain aspects of broadcasting with the iron fist of government decree, it played a passive role in the development of video recorders.

The Market Fails.

That allowed companies the opportunity to experience the alternative to standards based development. Rather than a government run organization establishing standards, individual manufacturers would all scramble to develop their own proprietary systems, optionally choosing to license their designs to other makers.

In hindsight, this worked out really poorly. While companies were already able to compete in delivering TVs that all worked according to the standard NTSC TV specifications, there were no standards guiding a record or tape delivery medium for video.

Because there were no standards, huge resources were wasted in competing efforts to invent new ones. This same principle was later relearned at considerable expense in the field of software development, in networking, and again in video standards. Open formats and open standards solve a lot of problems for the market.

It Worked in Audio.

The market had earlier appeared to work well in selecting audio formats, but there were fewer format to chose between and little real contention.

In the mid 60s, Philips introduced the audio tape, which put reel-to-reel magnetic audio tape into a compact cassette. It licensed the format to other makers.

An alternative format, the 8-track, came out at the same time. It was based upon the self-contained carts used in radio to record and play back jingles or advertisements while broadcasting.

Both tape and 8-tracks were widely popular though the 70s and into the 80s, but both offered lower sound quality than vinyl records; 8-track offered particularly marginal sound.

8-tracks slowly phased out as the smaller audio cassette tapes made portable players possible, leaving cassettes the lone ubiquitous standard for audio recording well into the 90s.

Why Video Tape Was a Problem.

The amount of information required to deliver a video signal is far larger than that required for audio, suggesting that any video tape system would have to consume huge reels of tape and draw the tape through the player at problematically unworkable high speeds.

Ampex developed the 2” Quad video tape format for broadcasters in the 50s, but it was far too large and expensive for home use. Ampex put video onto tape using recording heads that wrote in vertical stripes.

Researchers at RCA other companies had failed to deliver a workable video tape system because they were trying to record video using stationary heads that wrote horizontally like audio tape; they couldn’t move the tape fast enough.

Space Age Technology Tries to Replace Magnetic Tape.

Frustrated by the limitations of conventional tape recording and the high demands of video recording, makers turned to advanced new technologies.

In 1969, CBS developed the EVR, using optically read tape. Spools of film were unreeled inside the machine and read using a high speed scanner, which output a video signal for TV. It was outrageously expensive.

In the same timeframe, RCA developed the laser read HoloTape system which was also unworkably expensive, in addition to the more conventional MagTape system. After a test roll out of its prototype video tape recorders in 1974, RCA abandoned MagTape, deciding that it was too expensive to warrant continued development.

Germany’s Telefunken developed a flexible VideoDisc that went on sale in 1975; it was read using a diamond head like a record player. It offered very limited playback time.

Sony’s U-matic VCR in 1971 proved that magnetic tape was the most practical and economical technology for recording video.

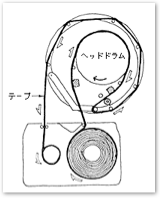

It used improved magnetic coatings on the tape, but also pulled the tape outside the cassette and around a rotating drum that wrote diagonal stripes on the tape, reducing the speed of tape required to deliver a video signal.

However, U-matic was delivered as a professional format and was too expensive for home users.

Additionally, the studios would not release affordable movie titles for U-matic, since there was no mechanism to audit rentals like the ill fated Cartrivision, or any way to stop users from duplicating films.

Sony wasn’t the only company offering consumer video tape recorders; in 1972, Philips launched its own VCR in Europe, which became the first successful consumer format.

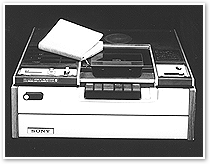

Sony’s 1975 Betamax format solved the cost and size problems of its earlier system by replacing U-matic’s 3/4” tape with 1/2” tape in a cassette about the size of a paperback book.

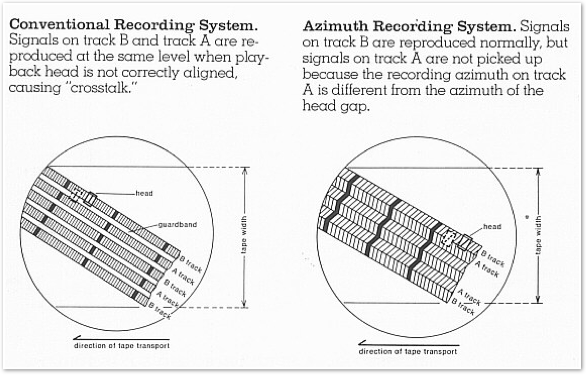

Sony also improved upon both Philips’ VCR and its own U-matic system by developing an azimuth recording head that could put tracks closer together on tape without suffering from crosstalk interference.

This enabled Betamax to reliably record a full hour of content on a single tape, something that Philips’ earlier VCR could not reliably do.

There were two remaining barriers to Sony’s efforts to establish Betamax as the consumer video format:

-

•the first was the Betamax Case, which MCA’s Universal Studios thew at Sony at the arrival of the Betamax VCR.

-

•the second was a play by JVC to hijack Sony’s technology and ship its own cloned version.

JVC Steals, Clones Betamax.

While JVC and other manufacturers had licensed Sony’s U-matic format, JVC decided to create its own rival format for home VCRs rather than licensing the new Betamax home format from Sony.

Sony wanted the industry to align behind a common standard. It had earlier worked with other vendors to develop consensus behind U-matic. It hoped that Betamax would launch a new revolution in home video, and tried to dissuade rival makers from introducing their own incompatible formats, fracturing the market.

However since U-matic had helped to establish Sony as the leader in professional video tape development, rival companies feared that licensing Betamax would only further entrench Sony’s position in the consumer market.

With full access to Sony’s technology, JVC created a slightly different cassette format called VHS in 1976. JVC’s rival format eventually won over the technically superior Betamax for a number of reasons:

-

•JVC initially offered a cheaper VCR

-

•Sony’s consumer and industrial divisions competed against each other instead of against competing companies

-

•VHS offered longer recording times than Betamax because its larger cassette could could hold more tape

Sony’s Big Beta Blunders.

Sony was shocked to find that its technical lead in video tape could be ripped off so easily by a former partner, but many of the Betamax problems were Sony’s own fault. Sony stacked the deck against itself by making a series of licensing blunders than sealed its fate back in the late 70s, before competition even got started.

-

•Sony turned down RCA’s advice to provide a long play mode, so RCA chose to license JVC’s VHS instead

-

•Sony withheld a Betamax license from Hitachi to avoid upsetting its existing U-matic partner Matsushita

-

•Matsushita chose to license VHS over Betamax because VHS tapes were simpler and cheaper to duplicate

That left Sony without the two largest players in the US and Japanese market. Sony continued marketing Betamax, and eventually delivered longer format versions that could hold two and then three hours of content, but VHS’ longer play had gained it a head start in video rentals.

JVC not only managed its licensing program better, but also ensured that all VHS licensees supported the slowest and highest quality SP mode, which ensured wide compatibility with movie rentals; Sony’s comparable B1 mode was not only too short to support an entire movie, but wasn’t even supported on all of Sony’s own players.

Content drove sales, and since Sony didn’t support various modes and prerecorded content on all of its Betamax players, VHS increasingly won ground with consumers, content producers, and manufacturers.

As VHS became established, it also logically became the medium for porn; it is unlikely that porn was a decisive factor however, because it is trivial to copy video between formats and low budget pornographers wouldn’t be stymied by the effort required to reach the Betamax audience in the same way larger studios would.

Sony’s advertising grew increasingly bitter and desperate as VHS gained traction, but it didn’t change anything.

Little Room For Technical Superiority.

In 1980, Philips followed up its original VCR with the VCC format, which crossed the VCR with its compact cassette tape design. Also known as Video 2000, the system used VHS sized tapes that could be flipped over like an audio tape, boasting recording times of up to 16 hours.

Philips’ system also pioneered dynamic tracking, which aligned the heads to the tape. Other systems had manual tracking controls until much later.

Even as early as 1980 however, there was little room left for a technically superior system. Prerecorded content was available for VHS, and manufacturers and retailers didn’t want produce and stock multiple types of tapes.

Unable to gain a real footing without content, VCC was also limited to the European market, leaving VHS the standard in consumer video tape players.

Sony eventually began selling VHS VCRs itself, and converted its Betamax technology into the Betacam professional format. Betacam records a much higher quality component signal, making it useable for professional broadcasters.

Sony later beat out JVC in consumer camcorders with the compact Video8 format. Designed specifically for use in small camcorders and using a flying erase head for cleaner edits than VHS could provide, Sony was able to win back the portable segment of the consumer video market in the mid 80s.

Sony repeated many of the same errors it made with Betamax in other formats it attempted to introduce, including 4 mm DAT and MiniDisc in the 90s, and more recently its ATRAC audio players, which handed the Walkman Dynasty to Apple’s iPod.

Videodisc Format Wars: A Quicker Battle.

While JVC won the video tape format wars, it was trounced in a parallel war involving prerecorded videodiscs.

In parallel with RCA’s failure in delivering magnetic video tape, it had also developed the SelectaVison CED videodisc, which electronically read vinyl disc media with an electronic contact head.

It suffered from problematic quality issues, but offered a picture better than video tapes, although not as good as Philips’ optically read Laserdisc, which Philips had developed in partnership with MCA as detailed in the article Movie Studios vs. Consumers in Home Theater.

JVC Again Tries to Pull a Microsoft.

Like Sony, RCA made the mistake of sharing its prototype videodisc with JVC in the early 70s; JVC took RCA’s technology and attempted to create its own rival standard, in the same way it had earlier hijacked Betamax video tape recording from Sony.

JVC had actually originated as the Japanese subsidiary of the American Victor Company, which was owned by RCA. During World War II, RCA cut its relationship with the Japanese Victor Company, but by the 70s, was again working with the company.

What RCA didn’t know was that JVC was the Microsoft of the 70s, intent upon stealing its research to develop its own incompatible, low quality standard it could foist on the masses.

Sure enough, JVC ran to to market with a movie and music player using two new formats incompatible with RCA’s original videodisc: Video High Density and Audio High Density; both even sounded similar to VHS.

Neither format caught on however. Philips’ Laserdisc was already superior on the video end to both RCA’s CED disc and JVC’s VHD copy. Further, Sony had also partnered with Philips to create the audio CD, which destroyed any chance of JVC winning the format war on disc with its copycat, technically inferior new record formats.

Manufacturers Learn to Work Together.

The vast wasted efforts suffered by Sony, Philips, RCA, and all their licensees who developed equipment that ended up incompatible and worthless to consumers taught the manufacturing industry the value of working together to develop common standards.

For the next generation of home theater, Sony and Philips agreed to drop their Multimedia CD standard to join JVC and a range of other manufacturers behind the Super Density disc, and effort that resulted in the highly successful launch of DVD.

Unfortunately it appears that that lesson has been lost, as the disc industry first splintered on ‘+’ and ‘-’ versions of optical disc recording technologies, and most recently on the next generation, high definition Blu-Ray and HD-DVD formats.

The Other Big Problem for Home Theater

Back in the mid 90s, it appeared that both the studios’ panicked fears of home theater users and the brutal format wars were nearly under control. However, one other critical problem still had to be solved:

The studios had worked so hard to differentiate movies from television and create an experience that could not be duplicated at home, that now--somewhat ironically--solutions needed to be engineered for the technical problems of presenting those movies designed exclusively for theaters on home theater equipment.

The movies that studios made available on both Laserdisc and video tape were often poor quality transfers from the original films; the next article takes a look, with less backstabbing and fight scenes, hardly any sex, but a fair amount of surprise endings, and quite a lot of artistic genius and brilliant engineering.

Like reading RoughlyDrafted? Share articles with your friends, link from your blog, and subscribe to my podcast!

Did I miss any details?

Next Articles:

Format Wars in Home Theater

Format Wars in Home Theater

This Series

Haloscan Q107

Format Wars in Home Theater

Sunday, April 8, 2007

Ad

Bookmark on Del.icio.us

Bookmark on Del.icio.us Discuss on Reddit

Discuss on Reddit Critically review on NewsTrust

Critically review on NewsTrust Forward to Friends

Forward to Friends

Get RSS Feed

Get RSS Feed Download RSS Widget

Download RSS Widget