Will Apple TV take off like the iPod? Just like the original iPod, Apple TV isn't designed to impress analysts doing reviews. There are few buzzwords to drop and little need for high priests to explain how it works. In typical Apple fashion, it just works, without really even requiring a manual. Whether it sells or not will have little to do with analysts' opinions, and more to do with how useful it is to consumers.

Here's a historical overview of the origins of home theater, leading toward a comparison of how Apple TV stacks up against previous and current generations of consumer home theater products.

Before home theater we just had the theater. At the turn of the century, the fledgling film industry quickly spawned movie theaters as a cheap form of entertainment. Not even Daddy Warbucks was flush enough to have a home theater; he simply rented out an entire show to watch a movie.

Early movies up into the 20's were filmed with hand cranked cameras without any sound, and delivered to theaters with sheet music for an organist to play during the film. New technology eventually allowed for both automated cameras and projectors as well as synchronized sound recording, ushering in a golden age of cinema.

There wasn't a huge choice in what to watch because of the overhead required to project a film and maintain a theater, but there also wasn't much competition in entertainment.

Television in the 40s.

The arrival of television would change that, but not immediately. TV was introduced to consumers during the Depression at a time when many Americans didn't even have electricity, let alone the money to buy an expensive entertainment novelty. Home entertainment was commonly limited to radio until World War II.

In the 40s, just as TV began to gain in popularity, the US War Production Board halted the manufacturing of consumer TVs for over three years. After that, pent up demand combined with the new post-war prosperity quickly increased the installed base of television, which in turn prompted the creation of new content to watch.

New TV content followed the existing pattern of radio: local affiliate stations broadcast television programming created by major networks, and supported their operations with local sponsors.

TV and Movies Fight For Attention in the 50s and 60s.

As TV became affordable, the movie industry scrambled to maintain customers. TV networks didn't commonly play movies; the TV networks developed their own content, acting as radio stations with a picture rather than a home version of the movie theater.

Still, the new availability of home entertainment ate into theaters' business. To attract customers, the movie industry invented a variety of new technologies that distinguished movies with:

-

•color picture

-

•widescreen display

-

•high definition picture

-

•stereophonic sound

Color picture: Adding color to movies was straightforward: use color film. Color production was more expensive, but it didn't cost theaters extra to show color movies.

Before color movie film became common in the early 50s, systems like Technicolor required capturing multiple reels of black and white film using color filters. Each reel of film was then soaked in a primary color dye and used to print a color version of the film.

Adding color to TV was more difficult. Early designs uses complex mechanical systems that projected images through spinning color wheels and aligned the picture using mirrors. Even after a simpler and backwardly compatible system for broadcasting color TV was standardized upon, it didn't magically upgrade the networks’ broadcasts.

Color support was not only more expensive to produce and broadcast, but also required far more expensive sets to watch it. Without an installed base of color TVs, it made little sense for broadcasters to upgrade all their equipment to support color. In fact, half of the American TV networks actually resisted the move to color.

Only two of the four major TV networks in the US were owned by TV makers, and one of them--the DuMont Network--was already going out of business in the early 50s.

NBC survived, and was left the only network with a real reason to produce color TV broadcasts; after all, NBC was owned by RCA, which had color TVs to sell. CBS and ABC had nothing to gain from selling Americans on color broadcasts, apart from enriching NBC's parent company and having to invest in expensive new equipment.

The high cost of color equipment and the lack of color content prevented color TV from gaining much popularity well into the late 60s, despite the technology having been invented back in the 40s.

That helped to make color in the movies a compelling reason to go to the theater. Another movie theater feature unavailable at home on TV was:

Widescreen display: Silent movies were originally shot at the standard 1.33:1 aspect ratio (4:3) commonly used by television. When sound was added, the Academy standardized on a compatible full screen ratio of 1.37:1, which allowed for a vertical soundtrack to be printed on the film next to the picture without creating a tall picture.

This standard aspect ratio was widened in three ways in the 50s and 60s to help differentiate movies from TV:

-

•anamorphic films are shot with a lens that compresses the picture on film. A anamorphic projector presents the movie at around 2.40:1. Fox developed CinemaScope as one of the first anamorphic systems and licensed it to other studios. One of the better examples of CinemaScope was Disney’s 2000 Leagues Under the Sea.

Panavision later replaced CinemaScope with an improved anamorphic system that is commonly used today. -

•wide film Instead of using Fox’ CinemaScope, Paramount developed its own system called VistaVision, which ran film through the camera to actually capture a wider frame using more film for a better picture.

-

•matted films simply block out portions of the original film to present a wider aspect ratio, creating a widescreen display by simply cutting the top and bottom and blowing up the picture.

In the frame below, the yellow box represents the widescreen version seen in theaters, and the red box shows what would be displayed on TV in a open matte version.

The shot has to protect for full screen display, as this scene from A Fish Called Wanda illustrates. The alternative is to pan-and-scan: crop a square area of the movie within the widescreen version--with the intent of capturing most of the action--and blow it up.

-

•multiple display films use more than one camera to capture extremely wide films. Cinerama originally projected three films from three projectors on a special wide screen. The shot from How the West Was Won shows two seams from the three projector system.

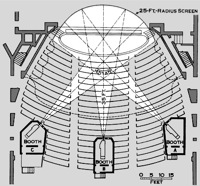

The widest films presented multiple cameras around a room to create a circle. Circlorama used eleven cameras; Disney built similar Circle-Vision theaters with nine screens in its theme parks--although most are now closed.

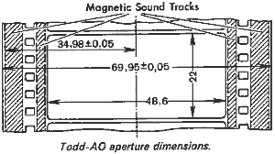

High definition picture: larger format films used larger film, commonly 70 mm, to deliver a clearer picture. Todd-AO filmed movies in 65 mm and distributed them used 70 mm film, providing extra space for soundtracks on the film. A few early Todd-AO films also used faster frame rates, which made action smoother on the screen.

This frame of a 70 mm print of 2001: A Space Odyssey shows how much more film area is devoted to recording each frame of the movie compared to the 35 mm clips above. In addition, the 70 mm film also had room for extra magnetic tape audio recordings on both sides of the sprocket holes.

Films shot in 3D can also be included with high definition. Like color and widescreen, 70 mm and 3D films offered an experience that couldn't be found at home.

However, the expense of filming in these formats, as well as the technical issues they created, limited their use. A film shot in Cinerama using three different cameras couldn't zoom in, for example.

3D films and other widescreen formats also required special projectors and screens in theaters. Without an audience of theaters, it made little sense to churn out movies using those features, and without the special content, there was little reason to build theaters that supported them.

A parallel example applies to audio reproduction.

Stereophonic sound: Stereo is typically thought of as two channels of sound using two speakers, but 'stereo' doesn't mean two, it refers to multi-dimensional depth.

Stereo sound relates to any system that plays back more than one channel of sound to create a surrounding, immersive reproduction of audio. Since wide, surrounding effects can be created with just two speakers, common stereo systems involve two recordings played back in concert.

This was another technology theaters could afford to add, while home users couldn't. Using analog tubes in radio or TV, the cost of playing back stereo sound doubled the price of equipment. It literally required a secondary receiver circuit, a second set of preamps, and so on, neatly doubling the cost of the set. Until electronic circuits could reduce the cost of all those components, it was simply too expensive. Stereo TV didn't become widely available until the 80s.

In the theater, the use of multiple sound tracks was a big draw. Disney's Fantasia used four sound tracks, and later 70 mm releases in the 60's put as many as 6 soundtracks on the film.

The 70 mm film strip here has 6 brown soundtracks in magnetic tape, played by the projector like a cassette tape.

In the 70s, several movies presented “in 70 mm,” including Logan’s Run, weren’t even originally shot on wide film; they were only printed to 70 mm to carry the extra magnetic sound tracks that couldn’t fit on 35 mm prints, where there was only room for four.

Theaters had to be outfitted to support playback of multiple channels of sound, and movies had to provide compatible, multichannel sound content in order to differentiate the theater from TV; the downfall of both factors helped to erase that advantage in the 70s.

The Decline of Movie Theaters in the 70s.

As competition from color TV began to eat into movie theaters' revenues, any remaining interest in rolling out expensive new technology in theaters began to collapse, killing much of the unique experience movies offered.

For example, many theaters were reluctant to invest in fancy sound systems to take advantage of the multichannel magnetic tape soundtracks glued directly on the film on some blockbuster movies, and commonly just played the movie's soundtrack in mono instead.

Theaters that had upgraded to fancier sound systems found the reverse problem: the magnetic tape soundtracks commonly wore right off the film after several showings, leaving little high quality content to play back using their fancy sound systems.

Increasingly, the multichannel magnetic soundtracks were replaced by two track optical sound, printed directly on the film. Below is a 35 mm print using 4 track magnetic sound, and a print with optical sound. The black graphic exaggerates the optical soundtrack for heightened dramatic effect.

As existing content degraded and fewer films were made using high definition prints or in true widescreen, the palace theaters of the golden age of movies began to disassemble themselves into multiplex outlets in order to at least offer more variety in the lower quality movies available.

The Rise of Home Theater Entertainment.

Many of the advancements pioneered in theaters had made it into the home by the 70s. Color TVs and color broadcasts was both commonly available, and FM radio had begun broadcasting in stereo. Both systems bent backward to support existing equipment.

Inside Apple TV described how color TV signals were designed to be backwardly compatible with black and white TVs.

In the case of stereo FM radio, a similar method was used. Rather than sending the new information as a separate subcarrier signal, FM radio takes the right and left audio channels and combines them into one sum or "mid" signal, and then subtracts the right and left signals to create a difference or "side" channel, and then modulates them together for broadcast.

This allowed older FM radios to play the sum channel in mono sound without losing any part of the broadcast, but enables stereo FM radios to demodulate both signals; they then add both signals to obtain the left channel, and subtracts the two signals to get the right channel. This form of matrixing turns up repeatedly as a strategy for delivering lots of information through a narrow pipe.

Enter the Audiophile.

Some aspiring audiophiles are outraged when they hear about this type of matrix encoding, sometimes called "joint stereo," because they imagine signals are being mixed together like paint, and suspect that the decoding to separate them probably isn't precise and doesn't involve enough gold plating on the connectors.

However, even vinyl records encode matrix stereo as mid and side channels; the mid is cut horizontally in the groove, and the side is cut vertically. Nobody would say that vinyl records don't deliver ‘true stereo.’

As home entertainment equipment to play back color and widescreen displays in high definition with high quality sound became available, it would seem likely that the movie studios would be quick to jump on home users as a new market for selling their movies. That wasn't generally the case however, as the next article shows.

Like reading RoughlyDrafted? Share articles with your friends, link from your blog, and subscribe to my podcast!

Did I miss any details?

Next Articles:

This Series

Haloscan Q107

Apple TV and the Origin of Home Theater

Friday, April 6, 2007

Ad

Bookmark on Del.icio.us

Bookmark on Del.icio.us Discuss on Reddit

Discuss on Reddit Critically review on NewsTrust

Critically review on NewsTrust Forward to Friends

Forward to Friends

Get RSS Feed

Get RSS Feed Download RSS Widget

Download RSS Widget