According to proponents of this myth, a vendor’s market share numbers speak for themselves as a critically important factor in selecting a technology product or platform. They're wrong, here's why.

Why the Myth was Woven

Market share is often used in spreading FUD. It has been used against Apple's Macintosh since its introduction over twenty years ago. Professional nay-sayers have long insisted that the Mac's limited market share would prevent it from benefiting from the hardware economies of scale that were driving PCs cheaper, as well as the widespread software development forces that were introducing a wide range of diverse PC applications.

Ironically, those making the biggest stink about Apple's historically low share of the overall PC market have started attacking the iPod’s majority share of the music player market. They gleefully preach the imminent demise of the iPod because its reported market share fell to 75% of all music devices. If market share is so critically important, why aren't the same analysts advising people to march out and buy the market leading iPod?

Ironically, those making the biggest stink about Apple's historically low share of the overall PC market have started attacking the iPod’s majority share of the music player market. They gleefully preach the imminent demise of the iPod because its reported market share fell to 75% of all music devices. If market share is so critically important, why aren't the same analysts advising people to march out and buy the market leading iPod? Clearly, this inconsistent use of facts to suit their purposes indicates something's wrong with the simple conclusions drawn from market share numbers. It also calls into question the credibility of those who use market share to make broad, sweeping generalizations.

Like most myths, there are elements of truth buried within the layers of wrong ideas. Let's pull apart what market share is, how it can be misinterpreted, and how numbers can easily be skewed to present false information.

Unraveled with Extreme Prejudice

The definition of market share is easy: it's the percentage of sales a specific vendor or product has within an overall market. Far more interesting, however, is the definition of the actual market in question, or the qualitative value of a given share of that market. These provide far more useful information, and are nearly always glossed over when base market share numbers get thrown around.

For starters, look at Apple's historical market share figures. Actual numbers vary somewhat depending on the source and its methodology. In this article, I'll consistently use numbers obtained from Gartner, and reference where and when the numbers were reported.

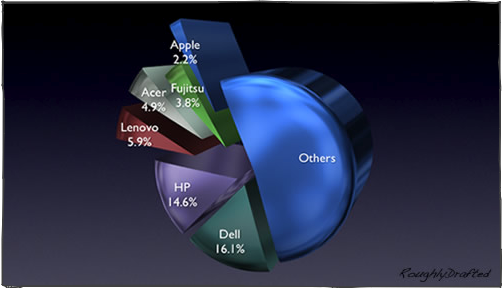

In 1980, Gartner reported Apple's worldwide share of the computer market at 15.8%. In 1996, they reported Apple's share as 4.6%. Last year, they reported Apple's market share at 2.2%. From those numbers, it would appear that Apple once owned vast control over in the PC world, and has been slipping ever since into a pit of irrelevance. That's the story FUD sprayers like to relate anyway. However, those numbers don't tell a very useful story without some considering their context.

Myth in the PC Market: 1980-1996

There was no PC in 1980, and there wasn't a Mac yet either. Computer makers were selling a brand new product category, and the vibrant and diverse market for home and business computers involved a wide array of machines made by various companies.

The market that Apple had a fifteen percent share of in 1980 was nothing like today's market. Only the flaming edge of early adopters were even buying computers, and mostly as a novelty. Still, there were far more than five major makers of computers, so Apple's share was very significant in comparison to its competitors.

Fifteen years later, Apple was at just under 5% of the market. According to the industry wags, this was because Apple had failed to broadly license their operating system to other vendors. Instead, Microsoft had blossomed as the provider of DOS software for the dominant IBM PC compatible market, and had just released a program for DOS that copied much of the look and feel of Apple's Macintosh.

Windows 95 was delivered late; it only arrived in the last days of 1995, so by 1996 it was just a few months old. Had it managed to capture 95% of the market in less than a single year? Obviously not. Apple's share of the market had drastically changed over the prior decade and a half not because Apple had dramatically slipped in popularity, but because the definition of the PC market had changed so significantly.

Between 1980 and 1996, PCs flooded into businesses, replacing calculators, dumb terminals, and paperwork commonly done by hand. Apple had made some ineffectual stabs at entering that business market, without much success.

Between 1980 and 1996, PCs flooded into businesses, replacing calculators, dumb terminals, and paperwork commonly done by hand. Apple had made some ineffectual stabs at entering that business market, without much success. In the early 80s, they targeted businesses with the release of the Apple III, which was a poorly built upgrade of their highly successful Apple II. It went nowhere, and Apple returned to building new variants of their Apple II line, which continued to sell well to schools and home users.

Apple's next generation of computers, the Lisa and Macintosh, were also aimed at the exploding business market. Their very unique software development required significant, new investment from developers, including mastering new human interface guidelines, far more than that required to create simple DOS apps.

The problems solved by the Mac's innovative new graphic interface were of obvious value to artists and designers, but less so to users who were simply entering data, and of little benefit at all to office drone workers who were simply connecting to an existing mainframe as a dumb terminal client.

Apple's Macs were so uniquely valuable to graphic designers that Apple could overprice their integrated hardware and software product and still sell lots of them. Their huge profit margins kept Apple flush with cash, and allowed them to further develop the Mac System Software, and work on new generations of wizzy product ideas like QuickTime and the Newton handheld, and share in the co-development of various successes and failures: PowerPC, Taligent, OpenDoc, A/UX, among many others.

While Apple was profitably selling as many Macs as they could build, a flood of generic, general purpose PCs were being rapidly deployed to serve markets Apple had neither the capacity nor the interest in entering. Apple would have been happy to sell businesses Macs running Microsoft’s Word and Excel applications, but businesses didn't want to pay for Apple's innovative software and premium hardware. They wanted a cheap substitute, and prior to 1996, that typically meant WordPerfect and Lotus 1-2-3 running on a basic DOS PC.

A low cost PC terminal with minimal functionality and an obtuse but simplistic text interface was a perfect match for the millions of office workers in cubes. Apple could have dropped their premium, innovative product to build PCs, but that would have thrown away Apple's clear edge in profitability and would have forced them to compete in a market only concerned with shaving the price of commodity hardware.

Alternatively, they could have tried to sell their Mac software to run on PCs in place of DOS, but this would have been problematic as well. They'd have to translate all their developer's efforts to PCs, without any way to create universal binaries. That would, out of necessity, kill their profitable hardware sales. NeXT tried this strategy and failed, even with their technology to deliver universal binaries.

Further, DOS PCs had low operating requirements, and could not have magically run a fully graphic operating system without significant upgrades. Who would this Mac software appeal to? Business users who didn't want to invest in Macs wouldn't have been much more likely to adopt Mac software if it would have similarly required them to beef up all their office workers' machines to do so.

The idea that Apple materially fumbled control of the PC world is simply a plausible sounding bit of speculative hindsight. If IBM couldn't introduce and establish OS/2 on their own machines, how could Apple have? Both NeXT's NeXTSTEP and Sun Solaris attempted to enter the PC operating system market, but failed to gain any traction for the same reasons: PCs in the early 1990's were crap that could barely run a graphical operating system.

Myth in the PC Market: 1996-2006

In the ten years following Windows 95's release, the Mac market share appeared to wilt from 5% to 2%, but those numbers similarly betray reality without considering some context. Apple is quite obviously doing better today, and has a brighter outlook for the future than they had in 1996, when they were at their lowest point of operational, technical, and strategic failure ever. How is it possible they now have less than half of their 1996 market share?

Prior to 1996, the PC market had already grown to include many market segments that had little to do with Apple, as noted above. So while their overall share of the PC market is useful in comparing Apple's performance to IBM, Dell, or Compaq, it is not material in considering the value or utility of Apple's product or platform.

If Apple had tried to build Windows PCs, or to compete against Windows as an operating system on PC hardware, those overall PC market share numbers would be very relevant, but Apple didn't. Here's why.

Microsoft managed, with some difficulty, to migrate DOS users to Windows in the second half of the 90's by tightly bundling DOS into Windows 95. That killed off any competition from alternative versions of DOS, while also making it no more expensive to run Windows 95: it was free with every new PC.

This is another example of Microsoft using exclusive software bundling to cheat the market, by wielding price as a competitive weapon against commercial alternatives without actually lowering their own prices. This is exactly the type of monopoly the US had a history of battling, but Microsoft managed to evade the enforcement of laws against predatory pricing until their position was so absolute that no competitors could effectively enter the market.

So not only had the hardware side of the PC market grown to encompass areas far beyond the market Apple was competing in, but the software side of the PC market had entirely failed to operate as a free market. The failure of the US Department of Justice to uphold the law had served to effectively turn Windows, the software side of the PC market, into a government sponsored monopoly.

A monopoly is not just high market share, but rather an exclusive position with the ability manipulate the market to prevent the natural balance created by competition. By killing the markets for DOS and Windows alternatives, Microsoft continued to enjoy fat profits without having to lower their software prices: there were no competitors!

A monopoly is not just high market share, but rather an exclusive position with the ability manipulate the market to prevent the natural balance created by competition. By killing the markets for DOS and Windows alternatives, Microsoft continued to enjoy fat profits without having to lower their software prices: there were no competitors!Low cost PC hardware tied to an expensive Windows software license created a closed market where demand for alternatives to Microsoft's software was suppressed by price dumping: potential competitors were competing against what appeared to be a free product.

The next time you hear market share numbers being thrown around, consider the context. Numbers don't speak for themselves, they require critical interpretation. Next up: more nails in the coffin of the Apple Market Share Myth: slippery numbers, quality vs. quantity, definitions of the market, and a closer look at iPod market share: Market Share Myth: Nailed!

| | Comment Preview

Read more about:

Read more about:

Send |

Send |

Subscribe |

Subscribe |

Del.icio.us |

Del.icio.us |

Digg |

Digg |

Furl |

Furl |

Reddit |

Reddit |

Technorati

Technorati

Click one of the links above to display related articles on this page.

The Apple Market Share Myth

Friday, July 21, 2006