Apple's Retail Challenge

By the early 90s, Apple's problem in selling its technology was already obvious. Computer sales were moving mainstream, out of specialized computer stores and into general retail.

Stores such as ComputerLand, which had sold a large segment of PCs during the 80’s, were falling out of fashion and being eaten up by big box retailers who offered a larger selection. They also offered lower prices, and along with that, little assistance for consumers.

Selling computers moved from a complex decision supported by knowledgeable, or at least enthusiast, sales people toward a shelf selection made by consumers with nothing more to guide their purchases beyond a list of specifications.

Thinking Outside the Big Box

As high volume, big box retailers provided increasingly less support for computer sales, their own price advantage was in turn eaten up by the even cheaper and more efficient mail order outlets.

In 1990, the then new Dell refocused itself as a direct mail order company; prior to that, Dell had struggled to sell its machines in warehouse club stores and specialized computer retailers.

By selling direct, Dell found new efficiencies over dealing with retail outlets. By cutting out retailers, Dell made greater profit margins, and throughout the 90’s grew rapidly until it outpaced Compaq as the largest PC maker late in the decade.

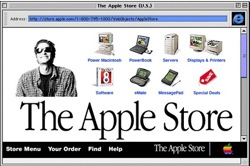

Online Retail with WebObjects

Dell expanded its mail order operations with an online web store using NeXT's WebObjects technology. This allowed Dell to build a sophisticated online operation that could handle high volume sales efficiently.

In an interesting twist of fate, Apple's acquisition of NeXT, while driven primarily with the intent of modernizing the Mac operating system, also brought NeXT's innovative WebObjects application server technology to Apple.

That left Dell struggling to build itself a replacement online ordering system using Microsoft’s problematic Active Server Pages, but allowed the new Apple to quickly roll out an online presence of its own.

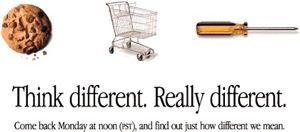

Less than a year after acquiring NeXT in the final days of 1996, Apple’s new store went online on November 10, 1997.

Logistical Challenges

More than just a new website, the online Apple Store involved a new manufacturing strategy that built systems as they were ordered, rather than just blindly building new machines, piling up large inventories, and then hoping to leisurely push it all out through the channel to resellers and eventually sell it all.

When NeXT took control of Apple in 1997, the company was losing a billion dollars a year, and was sitting on 70 days of unsold, finished inventory in various warehouses around the world and wasting millions of dollars warehousing and shipping around months of parts inventory between its manufacturing sites.

Apple Goes After Dell

When Michael Dell was asked how he would solve Apple’s problems at the Gartner Symposium in the summer of 1997, the Dell CEO said he would “shut [Apple] down and give the money back to the shareholders.”

Steve Jobs, in announcing the company’s new online store a few months later, Jobs referenced a photo of the Dell CEO and announced Apple would instead be targeting Dell, warning, "with our new products and our new store and our new build-to-order, we're coming after you, buddy."

In December of 1997, Apple announced that $12 million in online orders had been placed within the new store’s first 30 days of operation.

In a year, Apple reduced its unsold inventory from 70 days to a month, but the real goal was to outperform Dell and become the industry’s new leader in operational efficiency.

Jobs brought on Timothy Cook from Compaq, who simplified Apple’s operations and brought its parts inventory down to less than a day. Cook streamlined the number of suppliers Apple worked with, and got them to set up shop closer to Apple’s production sites. That allowed  suppliers to keep their own parts inventories.

suppliers to keep their own parts inventories.

suppliers to keep their own parts inventories.

suppliers to keep their own parts inventories.By working with fewer suppliers, Apple could offer each more business and in turn wield more leverage in making deals. In the next two years, Cook brought Apple’s inventory levels down to 6 and then just 2 days.

By 2000, BusinessWeek was singing Apple’s praises: “Apple. Yes, Steve, you fixed it. Congrats! Now what's Act Two?”

Stores Within a Store

While working quickly to establish an online presence, Apple also had to be careful to balance its direct orders with sales handled by its channel partners, other mail order resellers, independent dealerships, and the new relationship with CompUSA to build "stores within a store" with a focus on Apple products.

In the same press release advertising the success of its new online store, Apple took great pains to mention the importance of its retail relationship with CompUSA. After outfitting San Francisco’s downtown CompUSA store, Macs sales had jumped from 15% of overall store sales to 35%.

Apple also put its own employees to work in various chain retail outlets, acting to help inform customers and making sure that Macs were being displayed in working order.

Apple’s investment in store within a store retail with CompUSA was estimated to cost Apple between $25-75,000 each month, but it was delivering results that partnerships with other retail stores weren’t.

Retail Rivalry

Without its direct involvement, Apple recognized that Macs could not compete in standard retail stores while being sold next to PCs, because retailers could easily earn greater profits selling lower quality generic machines.

Retailers increasingly worked to sell their own house brand PCs which used even cheaper components than regular PCs. By building their own generic machines in house, retailers not only earned retail profits, but also made a higher overall margin by keeping the manufacturing profits as well.

That left many retailers with no incentive to sell Macs, and instead provided a powerful profit motive to convert customers interested in buying a Mac into the owners of a new, cheaply assembled, house brand PC.

This new cheap hardware fueled the Windows Price Paradox that autosold copies of Microsoft software on disposable, instant eWaste PCs that served to displaced Mac sales.

Rethinking Retail Partners

Between 1997 and 2000, the number of retail outlets offering Macs dropped from 20,000 to just 11,000. The majority of these were cuts made by Apple itself.

In 1998, Apple’s Cook announced the company would “cut some channel partners that may not be providing the buying experience [Apple expects]. We're not happy with everybody."

Apple then pulled out of Sears, Best Buy, Circuit City, Computer City and Office Max to focus its retail efforts with CompUSA. Apple later returned to Sears, only to pull out again in 2001. Apple also ended a shaky retail partnership with Circuit City in 2001.

The Challenge of Balance

The only brick and mortar retailers interested in selling Macs were those who made the majority of their operating profits from direct support and accessory sales: Apple’s existing dealer network and a few remaining chain stores with an Apple focus.

Retail stores’ profit on selling Macs is only around 9%. For resellers, that's hardly enough to make sales worthwhile, unless those sales lead to ongoing service and support contracts or regular sales of higher margin merchandise and software.

That put the majority of Mac retail sales in the hands of independent dealers with a business model centered around providing direct support for high value clients. However, while some dealerships provided exceptional service, the collective experience was inconsistent.

Without its own retail store presence, Apple would only ever be at the mercy of an independent group of dealers who didn't always share the same goals. Apple set out to assemble its own retail strategy, and by May of 2001 began opening its own stores.

Apple Bites the Hands that Picked It, from early 2004, described the conflict between Apple’s dealers and the company’s own retail efforts.

This Series

Wednesday, November 8, 2006

Bookmark on Del.icio.us

Bookmark on Del.icio.us Discuss on Reddit

Discuss on Reddit Critically review on NewsTrust

Critically review on NewsTrust Forward to Friends

Forward to Friends

Get RSS Feed

Get RSS Feed Download RSS Widget

Download RSS Widget