Apple TV: Using DVDs and other Video Sources

Apple TV isn't designed to play DVDs, but users have expressed enormous interest using it for that purpose, simply because DVDs are the most obvious and common source for movies, and many people already have a library of titles.

Here's a rather intense look at the complications involved in moving DVDs to the Apple TV, why QuickTime does not play DVDs itself, and the pros and cons related to four different options to getting DVDs on Apple TV.

Remember MiniDisc?

Imagine a hypothetical world where our audio CDs were all replaced by Sony's MiniDisc format. That would be awful: the audio data on MiniDisc is already compressed, so further compression of music for use as MP3s would result in lower sound quality.

Prerecorded MiniDiscs were also protected by DRM, making it difficult to get the audio off in the first place. Further, the Serial Copy Management System it used prevented users from making more than one generation of a digital copy from the original.

Those restrictions helped to kill the MiniDisc format, which was intended to replace cassette tape. Despite offering much higher audio quality and other compelling features, it simply couldn't do what consumers expected of it.

Something Worse than MiniDisc

MiniDisc's problems pale in comparison to the boondoggle that is DVD. Like MiniDisc, the audio and video content on DVD is already compressed, rather than being raw data like a CD. Also like MiniDisc, DVDs use DRM that complicates--but does not stop--content from being ripped from the disc media for other uses.

Unlike MiniDisc however, the DVD format offers no mechanism at all for making even a single digital copy. DVD not only uses the Content Scrambling System to create a technical barrier to getting content off the disc, but the industry has also employed the DMCA to create a legal barrier that prevents third parties in the US from offering tools that defeat CSS encryption. Europe has the EUCD, and other countries similarly enforce the WIPO Treaty.

In addition, DVD's compression and other technical specifications are protected by patents. Anyone licensing the DVD patent portfolio also has to agree to enforce rules related to region coding, encryption protection, and delivery. Some of these are truly draconian and outrageous:

-

•UOP, or user operating permissions, hijack users’ ability to operate their own DVD player, forcing them to sit through commercials and copyright warnings.

-

•Beyond UOPs, DVD menus force users to navigate often an poorly designed interface to play their content.

-

•Software DVD players must prevent any mechanism for grabbing screen shots from a playing movie.

-

•Region encoding creates territorial markets by preventing DVDs from playing in units sold in another zone.

Beyond DVD: An Ugly Vista

Despite the problems inherent in DVD, the vast improvement in quality over older VHS tapes helped make the DVD format popular. After establishing DVD, content producers hoped to migrate CDs toward the same style of overpriced user abuse that tramples fair use with the DVD-Audio format.

Microsoft worked to offer a similar system for ultra protected content with Windows Media and Janus DRM, essentially delivering all the DRM “features” of DVD, but tying the protected content to a digital lock on a PC instead of locking it to a physical disc.

For the next generation of HD discs, two rival camps are offering greater capacity and video quality on new discs that lock down content even tighter: Blu-Ray and HD-DVD.

These formats add new restrictions that not only prevent digital copying, but also force playback systems to shut down or degrade the signal if any part of the playback chain is determined to be insecure or isn't recognized.

Complaints about this new, heavy handed HD DRM have been a associated with Windows Vista, when it primarily relates to HD discs; Microsoft is just accommodating the entertainment industry in the same way it has ever since it discovered the vast sums of money it could make by tying all DRM content as tightly as possible to Windows.

Cracking DVD

People who really want to get things done aren't commonly flummoxed by technical or legal barriers though. When movies shifted to DVD, it induced hackers to figure out how to disable CSS to allow playback on Linux.

While credited to Jon Lech Johansen, aka DVD-Jon, the first effort to bypass CSS was developed in secret by at least five other unknown people; it appears to have involved commercial developers familiar with how DVD security works, who remained anonymous because claiming credit would have resulted in their being sued.

Despite the romantic portrayal of cracking and hacking common in the media, the encryption itself is rarely ever cracked; instead, users simply find ways around the otherwise onerous math that can be virtually impossible to defeat.

In the case of CSS, crackers were initially able to disassemble code from a software DVD player to obtain its player key. DVD-Jon simply reused the GPL code library others had written to publish the tool as a Windows app.

His popularization of the DeCSS code used to remove DVD encryption enabled others to determine how to bypass the CSS encryption without requiring a stolen key, resulting in a new project called libdvdcss, the basis for nearly every modern system that reads DVDs without the blessing of the DVD Forum:

Playing DVD

Peeling the data off of a DVD disc is only the first step however. After defeating CSS, the video on a DVD is still in an MPEG-2 Part 2 video stream, usually multiplexed with a compressed AC3 audio stream, and packaged inside of the MPEG-2 VOB container. More on what that all means in a moment.

Licensed and legal DVD players contain a player key to unlock discs, along with an MPEG-2 decoder to play the video and an AC3 decoder to play the audio.

Every licensed, commercial player, from the cheapest hardware units to the software DVD Player app included with Mac OS X, includes these components and must follow the rules established by the DVD Forum. If they do not, their manufacturer will lose its license to play DVDs and incur the swift legal wrath of the DVD Forum.

Playing DVDs Without Permission

Since there is no way for the open source community to license DVD technology and collectively agree to follow its rules and keep its secrets, there is also no legal way to play DVDs under Linux in most countries; the libdvdcss code has to be used to scandalously strip the CSS DRM simply to play DVDs on an open platform.

In addition to being illegal in most countries, it also exposes distributors to patent lawsuits. For this reason, most mainstream Linux distros including Ubuntu, Debian and SuSE do not distribute libdvdcss.

Apple obviously can't distribute this code in Mac OS X either. Even many rippers and open DVD player software projects require the user to obtain and install the code themselves from servers located in countries where it cannot be legally challenged.

This also helps to explain why QuickTime does not natively play DVDs; nothing can play DVDs without permission and licensing, or without venturing into problematic legal territory. The open source has no choice, but it also has limited accountability. The DVD Forum can’t sue unknown individuals working in other countries.

However, Apple is neither anonymous nor can it run to hide in foreign countries. If Apple added full DVD playback features to QuickTime, it would either have to determine ways to disable and thwart user rights within QuickTime to the satisfaction of the DVD Forum, or risk getting sued or barred from being able to play DVDs at all.

Instead, Apple delivers DVD playback through an entirely separate application, DVD Player app, which sandboxes those demands--including the inability to take screen captures during playback--within a limited environment. Apple pays the MPEG-LA for a license to distribute code that plays MPEG-2 data from DVDs exclusively within the DVD Player app.

Apple also offers a $20 Playback Component for QuickTime, which acts as a plugin to allow QuickTime to read MPEG-2 video for transcoding it into other formats. It does not have the ability to demux and decode AC3 or DTS sound however, nor can it handle CSS DRM, so it does not turn QuickTime into a full software DVD player.

Compressing DVDs

Once stripped of CSS using an application like MactheRipper, DVD files can be copied to a hard drive for playback via Mac OS X’s DVD Player, but those files consume an enormous amount of space: between 4-8 GB per disc. Just as with CDs, we need to further compress them in order to use DVDs conveniently without the disc.

MPEG-2 is a suite of specifications, split into different parts. There are three critical parts used in DVDs:

-

•Part 1 relates to Systems or container formats. MPEG-2 offers two different container formats:

-

•MPEG-TS or transport stream relates to digital TV broadcasts requiring error correction.

-

•MPEG-PS or program stream relates to video contained in files. It is the VOB container used on DVD.

-

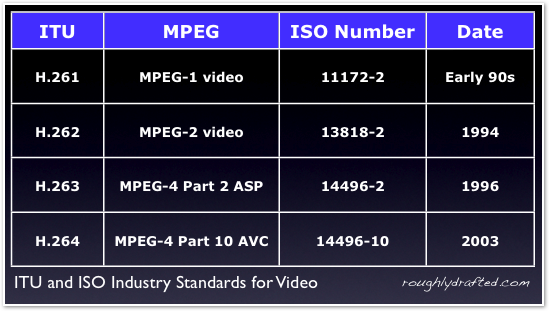

•Part 2 is the Video codec. Also called H.262; it carries ahead and improves upon MPEG-1 / H.261 video

-

•Part 3 is the Audio codec. This includes MP3 audio; it carries ahead and improves upon MPEG-1 audio

Both MPEG-2 Part 2 and 3 were designed to be backward compatible with the existing MPEG-1 standards, so that newer players could play back older content designed for MPEG-1. As technology progressed, backwards compatibility became less important than advancing the state of the art in compression.

MPEG-4: Small is the New Big

In 2003, MPEG-4 introduced two new advanced codecs that dramatically improved upon the technology available when MPEG-1 and 2 were originally designed.

Neither of the two earlier standards were optimized for low bitrate applications, making them poorly suited for Internet downloads and mobile devices that don't have a large disc to read from. The improvements in MPEG-4 also enable DVD video to be shrunken down to a more manageable size.

The Two MPEG-4s

However, the MPEG-4 suite also carried forward video compression that built upon the existing MPEG-2 Part 2 used by DVD, with more marginal improvements and retaining backward compatibility. This results in MPEG-4 delivering two very different sets of video codec technologies:

-

•1998 MPEG 4 Part 2 Video built incrementally upon MPEG-2; it is also called MPEG-4 ASP or H.263

-

•2003 MPEG 4 Part 10 Advanced Video Codec is a major jump over MPEG-2; it is also called AVC or H.264

The Two AACs

Just as MPEG-4’s H.264 leapfrogs MPEG-2 video, a new audio codec also leapfrogs MP3 audio, breaking backward compatibility with MPEG-1 and 2 to provide much better compression:

-

•MPEG 4 Part 3 Advanced Audio Codec is simply called AAC.

AAC is also a major jump over the AC3 Dolby Digital commonly used in DVD movies, and was designed by the same audio engineers at Dolby and other MPEG contributors. AAC is such a large leap over the MPEG-1 audio included in MPEG-2, that MPEG also added it to MPEG-2 portfolio:

-

•MPEG 2 Part 7 Advanced Audio Codec is the same AAC standard specified in MPEG-4 Part 3.

ISO Picks QuickTime

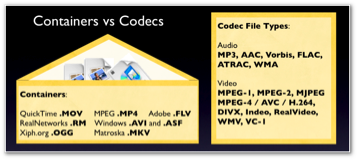

A third major change is the new MPEG-4 container format. MPEG-4 replaces the MPEG-2 VOB/MPEG-PS container with a new container based upon QuickTime's MOV movie container.

Microsoft's Plot to Kill QuickTime noted that the ISO chose Apple’s container format over Microsoft's ASF. Part of the reason for this was that QuickTime was proven, having existed since 1991. ASF has just been scrambled together as part of Microsoft’s ploy to edge out Apple using Avid: How Microsoft Pushed QuickTime's Final Cut.

QuickTime wasn’t just old, it was continuously supported; content from 1991 still plays back in 2007. Microsoft has repeatedly changed its promises and goals as it identified more lucrative markets.

Content created for Video For Windows will not necessarily play back in Windows Media Player, because Microsoft keeps changing its codec support and drops technologies as soon as they stop enriching the company. Microsoft has fooled a lot of consumers with its marketing of technology, but the E in MPEG stands for experts.

As Microsoft enraptured columnists like to point out, the industry doesn't like companies than can’t offer a plausible roadmap for the future. That’s why the entire industry aligned with Apple and against Microsoft.

Standard Alphabet Soup: MPEG, MPEG Good

The Motion Pictures Experts Group is itself a part of the ISO; MPEG isn't the only group working on video standards. The ITU, a telephony standards organization, has its own Video Coding Experts Group.

Rather that working at cross purposes, these groups have worked to share the same text in many of the standards they designate.

Apple likely refers to the latest standard as "H.264" to distinguish it from the multiple video codecs within MPEG-4, and because the ITU's numbering system makes more sense than rattling off "MPEG-4 part 10" or the even longer ISO number. Incidentally, the upcoming H.265 is planned for delivery around 2010.

The name others use for equivalent standards depends a lot upon who is using them and for what. CD-ROMs, DVDs and digital satellite broadcasts were all associated with the MPEG names, while ITU numbers were associated with the telephony industry; H.263 is most commonly associated with video conferencing.

Your Peanut Butter is In My Chocolate

In 1997, just as Apple began new efforts to reinvigorate development on QuickTime after years of little progress, things fell into place between Apple and MPEG that would mix two families of motion video technology together.

The MPEG group represents video broadcast experts. Apple, despite its 1994-1997 brush with death, still maintained the state of the art in time-based computer graphics development with QuickTime.

However, QuickTime lacked some technology used by MPEG to deliver broadcast video, and MPEG lacked technology Apple had developed for interactivity and multimedia compositing. As technology advancements enabled video and computing to converge, mixing those expert pools resulted in something better on both ends.

Your Peanut Butter: MPEG adopted Apple's QuickTime container format, which allows for a variety of data to be layered together in tracks: audio, video, text, images, VR, and wired interaction. New tracks can be defined and added as needed.

MPEG’s resulting MP4 container is nearly identical to Apple's MOV container, and QuickTime was updated to work with either one. QuickTime Streaming Server doesn’t even notice the difference.

All of the content Apple sells in the iTunes store is in the new MP4 format; file extensions hint at what’s inside:

-

•mp4 is video and audio

-

•m4a is just audio; aka standard AAC

-

•m4b is an audiobook; AAC with bookmarks

-

•m4p is protected audio; AAC with FairPlay DRM

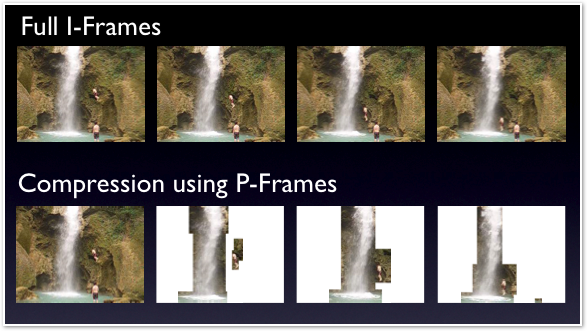

My Chocolate: QuickTime also adopted support for bidirectional video frames commonly used in digital video broadcasting. Prior to QuickTime 7, Apple's video technology only used:

-

•I-frames or intraframes, which present an entire picture and act as keyframes

-

•P-frames or predictive frames, which only present what has changed since the last I-frame

In a digital realm, the “film strip” doesn’t contain successive full frames; an I-frame is sent, followed by P-frames that only update what has changed. The original I-Frame is used to draw in the missing parts.

Advanced video codecs like MPEG-2 were also using B-frames, or bidirectional predictive frames. These present part of a picture like a P-frame, but reference changes relative to a future frame. In other words, B-frames come in advance of an I or P-frame that fills in the missing details.

To accommodate B-frames, the video decoder has to receive a series of frames, called a GOP or Group of Pictures, before it can begin drawing them. Using too many P or B-frames provides compression at the expense of failing to update the display properly, particularly in video with a lot of action.

B-frames add a sophisticated way to add compression, but it assumes that the video is only being played back. QuickTime was designed for editing, where video runs in both directions, not just in a straight line.

The concept of video frames arriving out of order required a significant reworking of how QuickTime decodes frames, in order to present this type of advanced compression in a filmstrip interface. It was a major new feature in QuickTime 7, although it was difficult to boil down into a marketing bullet point.

Adding these technologies together also melded the computing world of QuickTime with the broadcasting world of MPEG, making MPEG-4 uniquely suited to a new range of converged applications adapted for mobile devices, interactive TV, and Internet downloads while retaining sophisticated video compression techniques.

The DVD Bugaboo

Meanwhile, existing DVD movies are still in MPEG-2 formats. While QuickTime 7 was adapted to support MPEG video compression technologies, it still has the legal and technical barriers to playing DVDs as described earlier.

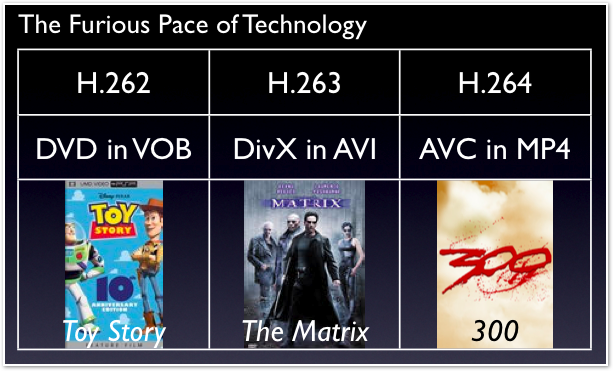

Prior to the advance of MPEG-4 AVC / H.264, hackers took Microsoft’s video codec, based largely upon MPEG-4 Part 2 ASP / H.263, and created their own version using the basic AVI container from Video for Windows. The result was DivX.

Since then, DivX (and a fork called XviD) has delivered newer versions fully compliant with MPEG-4 ASP, but all of those codecs are still based upon the minor advancements made to the old MPEG-2 video, and all still use the archaic AVI container format, which inefficiently wastes a lot of disk overhead.

That means the majority of video is either in MPEG-2 H.262 VOBs locked onto DVDs using CSS, or in some version of DivX MPEG-4 ASP H.263 in AVIs.

How does one get video to play back on modern devices using H.264 MP4s, such as the Apple TV?

Option 1: Just DVD Me

The easiest way to put DVD playback on the Apple TV would be to put DVD Player on it. DVDs could be ripped to disk and streamed in all of their huge glory to the Apple TV, filling its 40 GB disc with as few as five movies.

Pros:

-

•Compatible with AC3, DTS audio; DVD Player simply hands it off to the optical jack for external processing

Cons:

-

•Files are big, downloads are slow

-

•Requires rather drastic user intervention to install the app

-

•Doesn't integrate nicely with the Apple TV's interface

-

•It is unknown if Apple can put its DVD Player app on the unit, due to licensing terms or cost

-

•Requires users to rip the CSS off DVDs, which is legally a grey area and takes about a half hour

Option 2: DivX the Apple TV

Since many people already have DVDs ripped to DivX, another solution would be to copy the DivX codecs to the Apple TV. This gives QuickTime the ability to play DivX rips of DVDs; another third party plugin allows QuickTime to decode AC3 audio.

Reencoding DVDs to DivX requires some expertise because the optimal settings required depend upon the source material used. The broad range of options and performance tweaks available in the variety of DivX versions or in the various MPEG-4 ASP / H.263 codec implementations results in a wide variety in the quality of DivX rips.

That makes DivX akin to the state of pirate music in the MP3 world, the difference being that MP3s were mostly ripped from high quality, raw CD audio, where DivX movies are ripped from already compressed DVDs.

Another problem with trying to turn the Apple TV into a DivX player is that DivX rips aren’t optimized for QuickTime; most people use DivX with open source tools.

Those libraries support features missing in QuickTime, and may not support features unique to QuickTime. Conversely, QuickTime is being optimized for the next generation H.264, not for the many odd flavors of H.263.

Also, most DivX rips simply retain the original DVD's AC3 soundtrack, which DivX players typically just pass without processing. QuickTime wants to decode AC3 audio, and does not simply pass it out the optical audio port for external processing; even with our AC3 decoder plugin, QuickTime doesn't turn into a DivX-DVD player.

Pros:

-

•Allows a lot of existing content to be played

-

•Known to work, files are smaller.

Cons:

-

•Not compatible with the AC3 surround audio typical in DivX rips

-

•Requires rather drastic user intervention to install the app

-

•Doesn't integrate nicely with the Apple TV's interface

-

•DivX is not an optimal format for QuickTime playback and also uses the non-optimal AVI container

-

•Requires users to rip CSS off DVDs and then reencode them, which is legally a grey area and can take hours

Option 3: Install Linux or VLC on the Apple TV

Since QuickTime and DivX aren't the happiest couple, another option is to install VLC on the Apple TV, or alternatively wipe it entirely and turn it into a Linux box.

VLC (or another similar equivalent) delivers the useful libraries from open source without needing to jump to Linux, allowing playback and decoding with far more options exposed to the user compared to QuickTime.

VLC can demux about anything and play it, including AC3 audio directly ripped from DVDs. Unlike QuickTime, VLC will also pass AC3 audio directly to the optical outputs just as DVD Player does.

However, while it isn't too difficult to get other applications installed on the Apple TV, doing so complicates the device and its interface. A lot of the value of the unit comes from its simplicity. Further, the box is designed to be a low cost appliance, and it lacks the general purpose processing and RAM required to run a lot of applications.

VLC is a general purpose software player, and can’t take special advantage of the Apple TV’s graphics card the way QuickTime does for a specific set of optimized, H.264 encoded content. That means Apple TV’s limited CPU would throttle the performance VLC could deliver.

Pros:

-

•Fairly easy, known to work, files are small

-

•All sorts of customization possible

Cons:

-

•All sorts of customization required

-

•Requires rather drastic user intervention to install the app

-

•Doesn't integrate nicely with the Apple TV's interface and complicates the user experience

-

•Not integrated with existing software and can't be by Apple

-

•Requires users to rip CSS off DVDs and then reencode them, which is legally a grey area and can take hours

Option 4: Rip DVDs to H.264

Ideally, most Apple TV users want something that just works, or they'd already have hacked together a box on their own. The most ideal scenario for playing DVDs on the Apple TV is to rip them to H.264 files with AAC 5.1 audio, just like Apple uses on some of its HD movie trailers.

Purchased movie downloads on iTunes use 4 channel Dolby Surround. In either case, Apple TV outputs a signal that Pro Logic receivers can present in surround when using 5.1 speakers, or non-surround systems can play in normal stereo.

While Apple TV does provide multichannel sound for content mastered using Dolby Surround Pro Logic, most user-friendly ripping software does not yet support reencoding the AC3 5.1 on DVDs to either ACC 5.1 or to Dolby Surround, since there has never been a real demand for that before.

Apple's default settings for video output from QuickTime “to Apple TV” only support stereo, as Apple apparently thinks most users won't be converting movies from sources QuickTime does not normally play. That setting is intended to convert home movies and other simple QuickTime content to an Apple TV friendly format.

In order to push DVDs with surround soundtracks to Apple TV while retaining the surround sound, the audio has to be transcoded from AC3 to AAC or Dolby Surround.

Handbrake has been working for several months to add support for re-encoding AC3 as either multichannel AAC or Dolby Surround, and VLC already does. Using the AC3 decoder, QuickTime should also be able to do this.

Pros:

-

•Just works, files are small.

Cons:

-

•Requires users to rip CSS off DVDs and then reencode them, which is legally a grey area and can take hours.

-

•AC3 from DVDs does not playback in 5.1; must be converted to multichannel AAC or Dolby Surround first.

iPod vs Apple TV

Video capable iPods play H.264 content using dedicated video chips; the Apple TV plays back H.264 using QuickTime software, just like any other Mac. That means its slow general purpose CPU manages the job, but it appears designed to use Mac OS X's acceleration framework to delegate most of the work to the video processor.

That means that the iPod may be able to play some H.264 encoded video that the Apple TV can't. QuickTime's 'Output to Apple TV' setting should solve that problem, however.

The Legality of DVD Ripping

Will Apple ever be able to offer DVD ripping from iTunes? Most of the technical challenges appear to be handled, leaving only the legal questions remaining.

Reader Michael Long sent in a link to Eric Bangeman’s report on Ars Technica that Kaleidescape, a home server developer sued by the DVD Forum for building a system that rips user’s DVDs for playback, won the court case. Kaleidescape’s system stores a single copy of a user’s DVD in a copy-protected form for personal use.

That appears to open the door for Apple to offer DVD ripping in iTunes, creating a FairPlay-protected H.264 version of users’ DVDs that they can watch via Apple TV. This idea of a personal ripping server was included in my October 2005 Leopard Wishlist, so I’d be happy to see it delivered.

Other Content Sources

Reader Karl Lehensbauer writes, “Using PodTube or one of many other Applescripts floating around, you can snag YouTube videos, convert them to Quicktime and import them into iTunes in one step, either automatically syncing to Apple TV or streaming them from your Mac. It's the best way yet to show your favorite YouTube videos to your friends.”

Give the relationship between Apple and Google, we should see support for YouTube’s FLV and Google Video’s GVI formats added directly to QuickTime, along with either a browser in Apple TV, or way to download video content from Google and other sites directly in iTunes as an RSS feed, just like podcasts.

Incidentally, Adobe’s FLV Flash Video uses a proprietary VP6 codec, while Google’s GVI is just DivX in an AVI.

Like reading RoughlyDrafted? Share articles with your friends, link from your blog, and subscribe to my podcast!

Did I miss any details?

Next Articles:

This Series

|

|

|

|

Del.icio.us |

Del.icio.us |

Technorati |

About RDM |

Forum : Feed |

Technorati |

About RDM |

Forum : Feed |

Friday, March 30, 2007

Send Link

Send Link Reddit

Reddit Slashdot

Slashdot NewsTrust

NewsTrust