The last article, 1980-1985: 8-bit Platforms, looked at the rise of home computing and how new software titles established new platforms, from CP/M to the Apple II and the IBM PC. Here's a look at the next major jump in personal computing, which began in the second half the 1980's: the move to 16-bit platforms.

Platform Death Match introduced the difficulty of launching a new platform and the work involved in maintaining one. This series looks at the historical march of computing platforms, to sort out why winners won and why losers lost. While the computing environment is always changing, the same basic rules are in effect today, and will shape the future developments between Mac OS X Leopard and Windows Vista.

Previous article:

1985-1990: 16-bit Graphical Computing

Apple's Macintosh introduced a new wave of computing technology built upon the Motorola 68000 processor and a sharp, high quality graphic display.

Its innovative system software, parts of which was built into the Mac hardware, provided a ToolBox of standardized ways to draw on the screen, print to devices, work with disks, and interact with users.

This made it easier for developers to create a consistent set of new applications; developers could focus on building new tools rather than spending a lot of time trying to set up a basic user environment from scratch.

It also meant individual programs would no longer have to provide support for a wide range of specific printers. That lowered the bar, allowing smaller developers to release useful software that could compete against larger software houses. The operating system was taking over to provide more basic functions of the system.

Apple also defined system-wide standard keyboard commands and user interface guidelines so that all applications behaved similarly, making it easier for users to learn new applications, and reuse what they had learned in new programs.

While DOS programs already made use of keyboard shortcuts, each application made up its own set of commands, and most weren’t at all intuitive. For example, each of these DOS applications had its own way to open a new document:

-

•WordPerfect used the command F7 + 3.

-

•WordStar used Ctrl + K + O.

-

•Lotus 1-2-3 used / to open the menu, W for Workspace + R for Retrieve.

-

•Microsoft Word used Esc to open the menu, T for Transfer + L for Load.

On the Mac, every application used the same Command + O.

Apple also designated Z Undo, X for Cut, C for Copy, and V for Paste, and W to close a Window. Microsoft later adopted Apple’s intuitive commands for use in Windows over the existing DOS equivalents, although Windows still uses Alt + F4 to close a window. Since PCs didn’t have a Command key, Microsoft mapped the commands to Control.

At the time, DOS users were annoyed to have to unlearn their random commands to adopt the simplified, intuitive commands originated by Apple. Today however, Windows users often complain that Apple uses a Command rather than Control, thinking that Apple originated the change just to be oddball and different!

Notable platform lesson: Successful platforms create start foundations to build upon, enabling growth in new directions for both users and developers.

A New Market for Macs

Apple's new platform was no longer defined by a killer application, but rather by the look and feel of all applications designed to run on it. One of the premier developers of Mac software was Microsoft, who actually helped to define the standard Mac-like interface for a series of new office applications.

While the Macintosh wasn't defined by a killer app, it still needed one. When desktop publishing arrived, the Mac was positioned as an ideal system to lay out text and graphics for laser printer output. Unlike the earlier Apple III, the Mac was able to avoid legacy compatibility because it offered significant new improvements in both hardware and software. This created interest in the platform despite the lack of compatibility bridges.

It also helped that the first market that really adopted the Mac was entirely new: artists and designers hadn't widely used business machines, so there was no entrenched market leader to displace. Apple had a harder time getting the Mac into schools, which were already full of Apple IIs, or into business, where the PC was already entrenched as a standard.

Apple continued to sell schools and home users Apple IIs, and eventually released an Apple II compatibility card for the Mac LC; this was another stop-gap compatibility solution that served to shuttle users to the new platform, while really working to pinch off dependance on the old one.

Notable platform lesson: introducing a new platform is very difficult, particularly against an entrenched market. Finding an entirely new market can leverage growth towards establishing a sustainable platform.

In between, Apple managed to pop out a new platform that was a hybrid of the Apple II and the Macintosh: the Apple IIGS. It advanced the Apple II line into a 16-bit platform, and offered some of the same graphical toolbox features of the Mac, at an Apple II price.

The Apple IIGS was named for its new graphics and sound features. It was Apple's first graphics computer with color capabilities; the Mac still had a monochrome display. The Apple IIGS also provided the most impressive music capabilities of any home computer of its time via an Ensoniq sound synthesizer chip.

Largely the brainchild of Steve Wozniak, the IIGS also pioneered ADB, a Wozniak designed daisy-chainable serial bus for keyboards and mice that delivered many of the features of Intel's USB ten years in advance. ADB featured a hardware power on function in the keyboard, something that the newer (and faster) USB doesn’t.

Apple’s Mega II, which distilled all the hardware of the original Apple II onto a single chip, enabled the IIGS to maintain complete backwards compatibility with earlier Apple II software. It was later used in the Mac LC compatibility card.

Apple’s Mega II, which distilled all the hardware of the original Apple II onto a single chip, enabled the IIGS to maintain complete backwards compatibility with earlier Apple II software. It was later used in the Mac LC compatibility card.The Apple IIGS might have made a strong product for Apple if the Macintosh hadn't already been introduced. Instead, it fractured Apple's attention and developer resources by creating two platforms for the company to maintain.

The result was that support for the Apple IIGS was sporadic and half-hearted. Apple later delivered a new operating system for it called GS/OS, which borrowed additional technologies from the Mac and extended the capabilities of the Apple II line incrementally, but the Apple IIGS' days were clearly numbered.

Apple sold lots of the IIGS to schools, where its lower price and full compatibility with the Apple II made it easier to sell than the Mac. It also managed to demonstrate why full legacy support often is a bad thing: it turned out that most IIGS systems ended up being put to use as a slightly faster, 8-bit Apple II.

The result was that much of the IIGS' novel features and innovations were largely untapped by developers and therefore largely inaccessible to users. It never managed to gain a critical mass of IIGS-specific applications, partly because of Apple's increasing interest in promoting the Mac instead.

Notable platform lessons: supporting multiple platforms is a huge drain on development resources. Backward comparability may actually work to prevent forward progress.

The PC Market

Industry standard PCs trailed far behind the Mac, choosing instead to incrementally advance the old text based applications from the previous generation. Microsoft wanted Apple to deliver its new generation of graphical system software for the PC, but the earlier generation of text based computers weren't able to run a rich Mac-like environment. Microsoft itself struggled to deliver its Windows product for PCs, but had little success over the next five years until the release of Windows 3.1 in 1991.

As outlined in The Copy/Paste Development Myth, Microsoft's efforts to recreate the Mac environment on DOS PCs were more complex and difficult to accomplish than cleanly creating a new platform from scratch.

As outlined in The Copy/Paste Development Myth, Microsoft's efforts to recreate the Mac environment on DOS PCs were more complex and difficult to accomplish than cleanly creating a new platform from scratch. Microsoft spent twice as long developing Windows 3.0 than Apple did in delivering the original Mac! Why didn't Microsoft, now firmly entrenched as the driver of the PC industry, simply introduce a next generation PC on par with the Mac's cleaner and more elegant hardware?

Microsoft only controlled half of the PC product, so they were largely at the mercy of PC hardware developers, who didn't want to risk investing in a new platform. The PC platform has never been about innovation, only low prices.

That left Microsoft to copy the Mac environment on inferior hardware, where pixels weren't square, and might be drawn by any of several incompatible graphics card standards. Everything about PCs was oriented around being cheap, which ended up being very expensive for Microsoft to use as a foundation for their software platform.

Rather than one vendor offering a complete solution, the PC market represented a complex interaction of hardware built by a range of vendors, and operating system software sold primarily by Microsoft. Users had to pay the actual costs of integration themselves, a far higher bill than the original PC purchase price.

Notable platform lessons: supporting an integrated system is far easier than supporting a product of assembled parts from different vendors.

IBM hoped to contain its failure in losing control over the PC platform by introducing a new generation of PCs that used advanced, proprietary hardware standards IBM hoped to license to cloners. Called PS/2, the new machines introduced much faster MCA expansion slots, superior VGA graphics, use of the 3.5” floppy disk introduced by the Macintosh, and a new common standard for keyboard and mouse ports.

PS/2 also introduced a new operating system, built as a partnership between IBM and Microsoft, called OS/2. IBM thought it could climb back into the driver's seat with PS/2, but the PC industry had already grown too big for IBM to reclaim.

Other PC makers copied many of the PS/2's standardized features, but refused to pay IBM for a license and royalties to use MCA, and instead created an alternative PC expansion slot architecture called EISA. Lead by Compaq, the PC cloners left IBM on the sidelines.

PS/2 became a notable failure, and IBM suffered massive financial losses through the rest of the 80s. Not only did IBM lose hardware leadership to Compaq and later Dell, but IBM also ended up being abandoned by its OS/2 development parter Microsoft in 1990.

Simply inventing the PC platform didn't secure IBM's control over it. Even their technically superior PS/2 couldn't coax the PC genie back into IBM's bottle. Once the PC became a commodity market, all attention was focused on low upfront prices, and new innovation by IBM was either simply copied or ignored.

Notable platform lessons: an easy to copy platform will be copied. Once you give away your business model, it can't be easily reclaimed.

The Non-PC Market

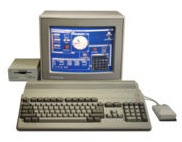

The basic concepts of using a mouse to handle documents presented in a windowing environment were also delivered by the Commodore Amiga and Atari ST on similar hardware to Apple's Mac, using the same 68K Motorola processor.

The Amiga uniquely used other specialized hardware processors that enabled it to excel in working with video and graphics. Atari differentiated itself from Apple mainly on price.

The Amiga uniquely used other specialized hardware processors that enabled it to excel in working with video and graphics. Atari differentiated itself from Apple mainly on price.The Amiga was originally conceived as a new game console, designed by a group of engineers who had left Atari. After Commodore dismissed Jack Tramiel, the company’s president and founder, Tramiel bought Atari, killed off most of its existing products, fired most of its employees, and made plans to release a next generation 16-bit computer.

Atari and Commodore ended up fighting over the Amiga group technology and over engineers defecting from Commodore to Atari. Commodore won the feud over Amiga, buying it up using profits from the C-64. Atari managed to get the ST in production first however, using a port of Digital Research’s GEM, a graphic desktop environment based on CP/M.

In the end, both the Amiga and the ST offered Mac like performance at a price comparable to or lower than the Apple IIGS. However, the relative size of both Atari and Commodore, and their inexperience in developing and maintaining a serious computing platform, meant that neither could really incite the third party development necessary to sustain a long term platform.

Keeping up with advancing hardware designs was difficult enough, but maintaining a full operating system with similar features to Apple was nearly impossible, particularly given the huge R&D Apple could invest into the Mac via hardware profits.

For example, while the Amiga offered unique feature advantages over the Mac, such as preemptive multitasking, it couldn’t attract enough mainstream third party development to really deliver that advantage to users. One key missing component was support from Microsoft for its Office applications.

The Amiga's advanced hardware features did find a niche market in video editing, motion graphics, and overlaying graphics on video. The Amiga ended up as an add on product that could be plugged into a PC or Mac, called the Video Toaster. Despite its lead in video, the Amiga couldn't keep up in other areas, and fell out of the running as the PC and Mac advanced.

Similarly, the Atari ST made inroads into European desktop publishing and CADD, but it wasn't enough of a market to sustain ongoing development, particularly as the 68k Motorola processor architecture ran out of steam.

Notable platform lessons: there is rarely enough room in the mass market for entirely new and incompatible platforms.

NeXT

Somewhat like Tramiel, Steve Jobs, after founding Apple and driving the initial Mac development, began to differ with Apple management on the direction of the company. After he was forced out of Apple in 1985, he left to create what he envisioned as the next step in desktop operating systems: a new development system that would be far ahead of what Apple had planned.

Jobs founded NeXT Inc., and several developers from Apple followed. NeXT decided that no available hardware platform could run the development system it planned to build, so NeXT made plans to build its own hardware platform and assemble its own operating system as well.

NeXT began delivering its new machines in 1989, jump starting the next epoch of computing.

Platform Perception vs. Reality

Apple advanced the state of the art in computing technology by decisively leaping into a new generation of hardware and software. The jump took enormous funding and risked certain failure, but resulted in a bold new platform that was clearly far in advance of commodity PCs, and rewarded Apple with new demand and profits, just as the previous generation of 8-bit machines demanded a replacement.

The Amiga, Atari ST and Apple's own IIGS all provided cheaper alternatives to the Mac, and had certain advantages, but all lacked the market and developer support to sustain them as viable platforms.

NeXT appeared poised to repeat Apple's performance, but similarly faced problems with finding a market or sufficient developer support. In many ways, NeXT was too far ahead of its time to enjoy widespread adoption.

Notable platform lesson: bold risks create the prospect of big rewards, but don't guarantee them.

The new generation of 16-bit graphical computers involved more complexity than the previous generation, which also demanded more investment from developers. However, the pace of technology continued relentlessly, quickly obsolescing these significant resources, and making new platforms increasingly difficult to introduce.

Attempts to rejuvenate existing platforms with new hardware and software foundations began in the next epoch of computing.

This Series

| | Comment Preview

Read more about:

Read more about:

Send |

Send |

Subscribe |

Subscribe |

Del.icio.us |

Del.icio.us |

Digg |

Digg |

Furl |

Furl |

Reddit |

Reddit |

Technorati

Technorati

Click one of the links above to display related articles on this page.

1985-1990: 16-bit Graphical Computing

Wednesday, August 30, 2006

Ad