Device Problems In Search of a Solution

A variety of consumer electronics devices present problems in search of a solution. Inconsistent user interfaces are key problem, but so is overall stability and the ability to painlessly sync with computers and networks.

Increasingly, devices store information that needs to be kept in sync, including calendar, contacts, and notes. Others access networks for content, including media downloads and software using web browsers and specialized web services. Nearly all of them need updates of some sort.

Other device issues deal with digital media, including cameras and music and movie playback devices. With the DRM protecting DVDs, how do users get their movies to work on a portable player? How does music get from a computer to a car stereo system to a mobile device?

Device Platform Problems

The problems PDAs and mobile phones suffer are comparable to the mess of incompatibility and complexity that plagued desktop computing in the 80's. The problems aren't all the same, but they similarly act to limit the usability and potential of consumer electronics.

User Interface

Mobile phone manufacturers have achieved incredible physical designs, have dramatically improved upon battery life, and deliver high quality cameras and other impressive features. However, inconsistency and complexity mute the potential of all that fancy hardware.

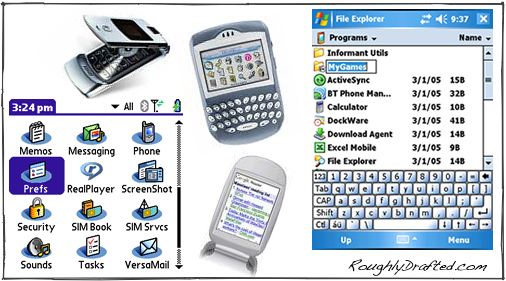

Over the last decade, both Palm and Microsoft have tried to solve these issues with the PalmOS and WinCE.

However, outside of the dying market for PDAs, both companies have ended up with slivers of the smartphone market, and efforts to build alternative tablet or kiosk devices have all been huge failures for both.

Stability

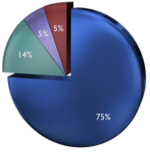

The reigning leader in smartphones is Symbian, which dominates the market with a share similar to the iPod's majority share of music players. Symbian is successful because it provides a highly reliable basic framework that can be used by various mobile phone makers to create highly customized interfaces. Linux takes second place in smartphones using a similar strategy.

The success of Symbian and Linux in the market has not resulted in phones with brilliant interfaces, but rather simply phones that work. The flexibility they offer manufacturers does nothing for users, who still end up with phones which provide a randomly designed user interface that bears no similarity with any other devices.

That problem was supposed to be solved by PalmOS and WinCE, both of which provide a standardized user interface. However, unlike Symbian and Linux, PalmOS and WinCE simply don't work.

They both frequently lock up and crash, and the very interface they intend to provide isn't that great. PalmOS is too simple and lacking in modern functionality, while WinCE is excessively complex and clumsy, a desktop OS stuffed into a small screen.

Data Sync

These devices also need systems to connect to for content and syncing. PDAs from Palm, or those using WinCE, have specialized software for data sync but are generally tied to a single computer. Keeping multiple computers and devices in sync is often problematic.

Mobile phone manufacturers provide their own sync tools, which often try to sync over a network, making it too complex and expensive to be practical. Various devices all sync using different software with unique interfaces.

Depending on the manufacturer or service providers involved, hardware functions may be crippled to protect business models. For example, Verizon has turned off Bluetooth features on some mobile phones to force users to spend their minutes using the company's cell network to transfer files, rather than being able to copy files directly to their PC for free.

Software is also an issue. Users want to pick a phone on features, not based on what software platform it offers.

Java intended to solve that issue by running everywhere, but rivals, including Qualcomm's BREW, have muddied the software landscape in efforts to enrich service providers by creating barriers to compatibility.

Verizon likes BREW because it offers a way to lock up the market for paid content and programming.

The result is that few phones are capable of running anything beyond a few gimmicky, overpriced games. PalmOS and WinCE phones can run a variety of specialized applications, if crashing and phone size isn't a concern.

Media Platform Problems

In addition to the latest mobile phones, an increasing number of devices now offer to play back music and video: portable players, wireless media extenders and libraries that deliver content to televisions and home theater installations, and integrated audio and display systems for cars and aircraft.

User interface problems also factor into these devices, as does media syncing and overall stability. The main problem for media platforms however is DRM. If the world were as simple as was back in the 80's, we'd still be using mix tapes in our Walkman players, our car tape decks, and in our home stereos.

Along with the digital revolution came new abilities and also new threats for commercial developers of songs and movies. The imagined panic of the early 90's that consumers would use their new ability to liberally distribute copyright material was proven true just a few years later as the web suddenly made it simple to mass distribute perfect digital copies across the Internet instantly.

The resulting lockdown of media under various draconian DRM systems effectively killed the market for early digital audio devices such as MiniDisc and DAT.

A decade after Sony's mistakes with excessive DRM lead to the failure of its new digital formats, Microsoft repeated the same mistakes in designing Janus, its DRM framework for digital files. Predictably, Microsoft's experiment in mistake duplication lead to the failure of its WMA digital media format as well.

Why DRM

Some consumers have decided the problem lies with DRM. However, DRM is merely a tool that serves a purpose. It has a bad reputation because most DRM efforts have gone irresponsibly overboard in destroying user rights under the guise of protecting copyright.

In reality, DRM is just a lock. Consumers are aware of why retail stores use locks to prevent theft. There are locks on the doors, physical locks on some merchandise, and sometimes electronic tags that trigger inventory alarms.

Everyone knows there are no locks or security systems that are impossible to outwit, but retail locks do work to block the majority of theft related loss retailers would otherwise suffer. The theft they help to stop also prevents retailers from having to cover their losses by raising prices.

In the digital world, DRM serves the same purpose. It can be a functional deterrent to mass theft without being an insane barrier to normal use. When abused, DRM fails, just as it did for Sony's MiniDisc and Microsoft's PlaysForSure, and just as its now doing for the Zune.

When DRM is created to serve the needs of both producers and consumers, it works to create markets; DRM creates a product that can be sold, creating demand for content that would otherwise be unavailable.

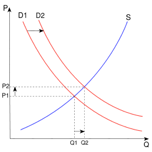

With real goods, the scarcity of a product is what makes it valuable; it has value because of its limited supply. If the supply increases, the price drops. Lower prices mean there is less reason to produce it, which eventually results in a lower supply and higher prices.

The value of intellectual property is not based on the scarcity of a product, but in the scarcity of good ideas to put inside a product. The supply and demand forces that affect production and determine value to set prices have little to do with CD blanks or MP3 files that can be infinitely duplicated at near zero cost.

There is no physical scarcity involved with digital bits that can be freely duplicated. The value in music, movies, and other content is in the talent needed to originate, produce, and manage intellectual and artistic work.

Without DRM acting to turn content into a product that can be sold in the same manner as other physical goods, there is no market because there is no way to establish a price using supply and demand.

DRM And Markets

Chaos and uncertainly are devastating to markets; consider trying to run a retail business during a riot without locks or any police protection. And consider the potential for markets if currency could be freely copied. In the US, the main role of the Secret Service is to prevent the counterfeiting of money.

Using markets to set a fair price for digital media is similarly impossible if users can artificially and illicitly inflate supply and glut the market with counterfeit copies on a whim.

Ignoring the recent grandstanding by Yahoo! to sell a single track as an MP3, few commercial producers are willing to offer songs and movies in a wholly unrestricted form; its the same reason that money is printed with anti-counterfeiting features.

The musicians that do sell their work as unrestricted MP3s are in the same position as software developers who offer their work as shareware. Unfortunately, both are rarely able to afford to live off the proceeds they get.

The less status a producer has, the more willing they are to offer their work without limitation. Conversely, the more popular and prominent entertainers and developers become, they harder they work to actually get paid by their users. The result is simply that major commercial producers of music, television, and movies demand DRM to protect their work from mass duplication.

Two Extremist Perspectives on DRM

Without a fair and functional system of DRM, the world would be stuck in the same struggle that prevented markets from developing through the 90's: an ideological battle between the foes of any form of DRM at all, and the equally ridiculous producers who have similarly unrealistic ideas about the value of their content and how tightly it has to be locked down.

-

•

Media producers who like to delude themselves into thinking that their software, patents, music, movies, or other intellectual property is so unique that it has near infinite value and can command any price they want.

Media producers who like to delude themselves into thinking that their software, patents, music, movies, or other intellectual property is so unique that it has near infinite value and can command any price they want. -

•Peanut gallery freeism fanatics who think that anything that can be duplicated at little cost effectively has no inherent value, and should be free for anyone to obtain, copy and redistribute.

Fair DRM

The very idea of "fair DRM" is no doubt considered to be an oxymoron by those who have no respect for intellectual property. Unfortunately for them, the owners and producers of music and movies don't care.

In fact, the market itself doesn't really care, because people who don't respect the law don't materially participate in the economy anyway.

Trying to sell DRM to foes of intellectual property is as pointless as trying to make sure burglars pay for items they take as they flee a store. Fortunately, most consumers are willing to pay for the things they want. Fair DRM allows them access to the content they want in exchange for a set price that makes sense.

For DRM to work, it has to be understandably consistent, not subject to unreasonable unilateral changes, and offer fair pricing.

MiniDisc failed because its DRM prevented customers from using the system in expected and reasonable ways. PlaysForSure failed for similar reasons, but also introduced too many options, so users had no assurance that music they bought would consistently play back, burn to CD, or continue to work past the end of the month.

A Consistent Problem

Uncertainty kills markets. Unprotected music distribution creates uncertainty for producers. Excessive and burdensome DRM creates uncertainty for consumers.

In fact, the common thread behind all these device problems in search of a solution boils down to consistency:

-

•Consistent User Interface

-

•Consistent Stability

-

•Consistent Data Sync

-

•Consistent and Fair DRM

It just so happens that consistency is Apple's core competency, and the platform Apple is building will extend consistency throughout digital devices the same way the Macintosh solved the problems of inconsistency in early computing. The next segment will explain how.

Next Article:

This Series

Tuesday, December 12, 2006

Bookmark on Del.icio.us

Bookmark on Del.icio.us Discuss on Reddit

Discuss on Reddit Critically review on NewsTrust

Critically review on NewsTrust Forward to Friends

Forward to Friends

Get RSS Feed

Get RSS Feed Download RSS Widget

Download RSS Widget