1990-1995: Microsoft's Yellow Road to Cairo

Automatic PC sales of DOS rapidly made Microsoft one of the largest software companies of the 80s. As its market power increased, it gained a reputation as a vendor with staying power. Nobody wanted to invest in the software of a company that might go out of business.

Microsoft used its new clout to introduce a product vision called Cairo in 1991; it disrupted development and marginalized competition throughout the next decade.

The tactic worked so well that Microsoft repeated it in the following decade as Longhorn. Here's how it happened, and why Microsoft won't be able to repeat the same fraud again.

Platform Death Match introduced the difficulty of launching a new platform and the work involved in maintaining one. This series looks at the historical march of computing platforms, to sort out why winners won and why losers lost. While the computing environment is always changing, the same basic rules are in effect today, and will shape the future developments between Mac OS X Leopard and Windows Vista.

Previous articles:

-

•1990-1995: Why the World Went Windows The smart strategies and dirty tricks used to establish the PC.

-

•1990-1995: Platform Crisis: The Tentacles of Legacy Balancing past compatibility with future technology.

-

•1990-1995: Platform Crisis: The Lazy Dinosaur Apple and Microsoft get lost in a rapidly changing world climate.

1990-1995: Microsoft’s Yellow Road to Cairo

Along with Ashton-Tate and Lotus Development, Microsoft was considered one of the Big Three software developers of the 80s. Apple courted all three to develop software for its new Macintosh.

Ashton-Tate managed to run itself out of business, and Lotus was eventually bought up by IBM in 1995, leaving Microsoft as one of the largest and most influential developers of desktop applications.

Microsoft's position as a vendor for both DOS and office applications gave it certain advantages over its rivals, particularly when Windows 95 appeared and obsolesced not just previous versions of DOS and Windows, but also competing developers’ existing applications, including DOS standards WordPerfect and Lotus 1-2-3.

Rapid advancements in technology created a wildly chaotic market, where simple announcements of future plans could trump real products. Given the prevalence of misinformation wars in the tech industry, it's no surprise that Microsoft applied its vast market power to become one of the most notorious sources of FUD and vaporware.

Innovations in Vaporware

Previous articles have considered Microsoft's vaporware attacks on QuickTime and the Newton and PenPoint OS.

While many companies in the competitive tech field announced products they were ultimately unable to deliver, Microsoft applied an innovative, two handed approach to playing the vaporware game.

Rather than just bluffing its hand like other companies, Microsoft played the game with a set of cards in one hand, while waving the illusion of another set of cards in the other hand. The fake set of cards were highly distracting because they looked like a much better hand than anyone else could possibly have.

Standing around the card table were a number of analysts who all expressed how impressed they were by the cards Microsoft waved in the air, and made regular remarks about how foolish it would be for anyone else to stay in the game. The worst part was that many of those analysts could see Microsoft's real hand, and knew the company was bluffing.

Microsoft's NT Plans Prior to Cairo

In 1991, Apple was releasing the Mac System 7 and Tim Berners-Lee was using his NeXT to build the world's first web server and browser.

PCs were still using the character based DOS in a slightly faster version than was released a decade earlier in 1981, although Windows 3.0 was beginning to provide DOS PC users with a rough approximation of Apple's graphical desktop.

After witnessing sales of Windows 3.0 take off, Microsoft began its schism with IBM over OS/2 3.0 development. Microsoft's new plan involved an entirely new operating system based on its contributions to OS/2; the new OS was referred to as Windows NT.

Unlike the existing DOS based Windows 3.0, NT aimed at being entirely new and modern in every respect, untied to DOS or to the existing x86 PC architecture.

Microsoft initially targeted NT to run on the i860, Intel's new 64-bit RISC processor that was supposed to usher in the future. The i860 was a modern design and carried none of the legacy baggage of the standard x86 based PC.

It included graphics acceleration features similar in principle to the forthcoming PowerPC Altivec and Pentium MMX; those features resulted in the i860 being used by NeXT to power its high end NeXTDimension video card.

Unfortunately, the i860 didn't work out for Microsoft. All that remained from its efforts to build a new operating system based on the processor was the i860's code name: N10, which is widely repeated to be the meaning of NT. Of course, Microsoft and IBM had also long referred to OS/2 3.0 as "NT," for new technology, so the idea behind the i860 as the source of NT's name might be historical revisionism.

No Operating System Experience

Microsoft struggled with the complex reality of building its own operating system without IBM. Up to that point, Microsoft had only been delivering tepid updates to MS-DOS, which it had licensed from a small developer. That original product, QDOS, was based on a clone of Digital Research’s CP/M.

Prior to DOS, Microsoft had originally tried to sell Xenix, a version of Unix it had licensed from AT&T in 1979. Xenix eventually turned into today's SCO UNIX.

Despite quaint stories about Bill Gates singlehandedly writing DOS on the back of a napkin, Microsoft had no real experience in building or designing operating systems at all. Throughout the second half of the 80s, it had relied on IBM to develop OS/2 as the replacement for DOS.

Sales of Windows 3.0, a DOS application, suggested that Microsoft could make more money without IBM by simply licensing an underlying OS for the Windows environment, or hiring a team to write a new one in house.

That turned out to be a bigger task than anyone at Microsoft had imagined. In 1988, Gates had recruited a development team from DEC, headed by Dave Cutler, initially to work on the next version of OS/2. In 1990, Microsoft officially set Cutler loose on building a new OS kernel for Windows to use in place of IBM’s OS/2.

That effort resulted in Windows NT, which was eventually delivered many years later than initially planned. In trade magazines of the day, NT was joked to stand for “Not on Time.”

But Wait, There’s More

With its NT project moving along slowly, Microsoft invented a much rosier view of the future under the code name Cairo. Shortly after it planned to ship the first version of NT, Microsoft said it would deliver Cairo, a product that would not only leapfrog NT, but also anything that Apple, NeXT, or IBM were already offering.

Cairo was Microsoft’s Pink: a cloud of ideas that was talked about as a specific product, a series of products, then eventually just as an overall strategy or vision.

While Apple’s Pink was constrained by legacy realities of the existing Mac System 7 market, Microsoft Windows 3.0 was barely a finished product in 1990, with very little Windows specific software available, particularly from major developers. That allowed Microsoft the freedom to paint out Cairo any way it desired on a clean canvas.

Slippery Plans and Brands

Many of the terms and brand names Microsoft used shifted over time or as its strategies changed. This creates some confusion in retrospect.

Prior to 1990, Windows was described as a programming and user environment intended to be folded into the new OS/2; in the interim, it could run on DOS.

At some future point, the world was supposed to trade in the essentially free-to-obtain DOS with a paid $200 copy of OS/2. That would enable PC users to run the software designed for DOS and Windows they already could run, as well as new software native to OS/2 that they did not have and did not yet exist. Hmm.

It's amazing that neither IBM nor Microsoft seemed to worry that this strategy might not work out, but everything is much clearer in hindsight. OS/2 was the first attempt to deliver a new platform for the PC; Apple had earlier learned about the difficulty of moving customers to a new platform with the Apple IIGS and the Mac.

At the time, nobody was really selling desktop operating system software at retail. Apple had historically given away updates to the Mac System Software, and had just begun its own attempts to turn System 7 into an actual retail product it could sell. As it turns out, consumers aren't usually very interested in buying software unless they have to, particularly unsexy utility software.

In 1990, when sales of the DOS based Windows 3.0 took off; it allowed the PC to rather cheaply be used as a poor man's Macintosh for graphic applications such as PageMaker. That prompted Microsoft to pull out of its OS/2 partnership with IBM, and focus its efforts on delivering its own new OS kernel, in parallel with the ongoing development of Windows.

Microsoft's new operating system to replace DOS was called NT, a name that had earlier applied to the upcoming third version of OS/2. Windows still referred to the user environment that would run on top of NT. IBM also continued its own plans to make sure existing Windows apps would continue to work on its OS/2.

For NT, Microsoft began work on a new 32-bit version of Windows. This environment was called Win32, and the existing Windows was renamed Win16. That change left IBM supporting an old version of Windows, and made Microsoft the only source for running the new and more powerful Win32 applications.

It also gave Microsoft the inside track in developing Win32 applications. Other developers selling competing PC desktop applications complained that they could not get equal access to information on how to write the new Win32 apps, particularly the secret APIs that Microsoft used to deliver its own apps, principally Office.

Two years before it first shipped Windows NT as a product, Microsoft began describing Cairo as the next generation of Windows NT. Rather than a simple graphic shell running Win32 on its new, unreleased, and unproven NT kernel, Cairo would offer an entirely rethought, futuristic new architecture, from its core OS and file system to its new user environment.

Distracting Vapors of the Future

This was important for Microsoft to announce, because the existing Mac user environment from Apple, and the existing development environment and operating system technology from NeXT were both clearly far in advance of what Microsoft Windows currently offered, or could be expected to offer in any reasonable time frame.

Cairo, like Apple's Pink, was vaporware. It was a loudly announced vision of the future to distract from the current realities of the market. Just as Apple's Pink was supposed to eventually match all the things NeXT had already delivered, Microsoft's Cairo announced things that would not be deliverable for a decade or more.

Microsoft simply had no car worthy of competing in the race, so it drew up an impressive picture of flying race rocket instead. The press, impressed by this compelling Cairo illusion, stopped comparing the ridiculously lame Windows 3.0 and DOS to the contemporary Macintosh and NeXT, and instead began comparing Apple and NeXT’s existing products to the future promises of Cairo.

Even NeXT believed Cairo would turn up eventually.

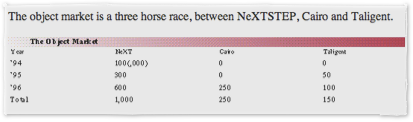

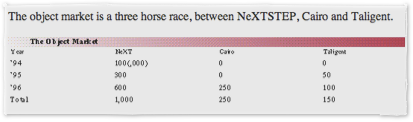

The company plotted out charts showing how it planned to compete against the imminent arrival of both Taligent and Cairo.

Like other victims of vaporware, NeXT had trouble selling reality because everyone only wanted to hear about Microsoft’s fictional plans that would not end up getting delivered for another half decade or more; significant parts of Cairo would never be delivered at all.

Unhindered by Reality

Without having to accommodate legacy compatibility with existing applications, and artificially isolated from having to compete in the market against real opponents, Microsoft was free to imagineer a magic future for a world ready to believe that everything Microsoft could plan would be delivered at some point, even though Microsoft had absolutely no history of delivering any significant or original operating system technology.

Microsoft's distraction hand was waving a hand of five Aces, but rather than questioning how that could even be possible, the press just gushed about how great Microsoft's future looked. The company's bluffing was actually empowered by the uncritical appraisal of the press, which only encouraged Microsoft to continue in announcing unrealistic plans.

Time or resources would not be a factor, because this was the computer industry! Time to deliver could be infinitely shortened by simply hiring more engineers to work on the project, and resources were irrelevant because of the economies of scale working in Microsoft's advantage. By suspending basic logic, everything made simply made sense.

It's just like putting a cake in the oven and setting the temperature to twice as hot as recommended: obviously, the cake will be done in half the time. Or so news analysts said.

Cairo: Buzzword Compliant

Cairo described a new OS and user environment bathed in the industry buzzwords of the day. It also borrowed heavily from the ideas of existing competitors. After all, if other companies were already selling this technology, it shouldn't be difficult for Microsoft to duplicate it. Or so they said.

Specifically, Cairo promised to deliver:

-

•an object oriented user interface, featuring direct manipulation of desktop objects like OS/2 already had

-

•an object oriented development environment like the one already offered by NeXT

-

•distributed computing features like those offered by NeXT

-

•an object or database file system that would replace the flat file system with a fully searchable object store

-

•a standards based messaging system like Lotus Notes

-

•a standards based directory system just like Novell's NDS

Failure to Launch

Microsoft’s Cairo ended up being perpetually a year or two away from release until the company stopped talking about it in the late 90s.

In 1992, Microsoft said it expected Cairo to debut in 1994. The next year, in 1993, Microsoft delivered the first version of Windows NT, which was given the version number 3.1 to position it as the obvious successor to the DOS based Windows 3.0.

The NT kernel was generally considered to be well designed, so much so that DEC accused Microsoft of stealing its proprietary software technology when it hired away Dave Cutler to build the new OS. However, the original NT didn't perform well on standard PCs, which lacked the resources to run it.

That sent Microsoft scrambling for an interim plan. It dusted off the DOS based Windows 3.0 and improved it enough to act as a placeholder until NT could be fixed. Microsoft hoped to call its next version of NT "4.0," so the new version of DOS based Windows was called “Windows 95” rather than being named after a version number.

Even shipping Windows 95 became a difficult task. In early 1994, Jim Allchin announced that Microsoft was reassigning more programmers to work on Windows 95, and that Cairo would be delayed until late 1995.

By the end of 1994, Microsoft Vice President Mike Maples was quoted as saying that Cairo would slip again, to "sometime in 1996."

A year later, at the end of 1995, Microsoft shipped Windows 95 with what it described as a subset of the Cairo user interface. However, Windows 95 didn't offer the world anything new in user interface technology. It copied liberally from both the Mac and NeXT, and was commonly criticized in the phrase "Windows 95 = Mac '89."

At the release of Windows 95, Microsoft announced that a "first test version" of Cairo would debut in late 1996, with the actual release happening in 1997, more than half a decade after its original announcement.

By 1996 however, Cairo was being described as a vision instead of a real product. In a Computerworld interview, Bill Gates said, "Cairo is a futuristic system. It's something we're working on."

After a half decade of being presented as a legitimate competitor to NeXT's object oriented development tools and various other products, Cairo was revealed as a complete hoax.

Microsoft had fooled the world with a story about delivering the equivalent of NeXT only a few years late, but only ended up shipping a rewarmed version of the 1990 DOS based Windows, and an unworkable, unstable new OS kernel in NT that was not ready for prime time.

Cairo's Old New Vision

In 1996, Microsoft released Windows NT 4.0. Components of Cairo's vision, including the Object File System for NT and what would become Exchange Server, were abandoned for a more conventional file system.

NT 4.0 also used the same Windows 95 interface. More problematically, Microsoft made major architectural changes to NT 4.0 to make it faster, which actually seriously compromised its design; more about that later.

Other parts of Cairo still weren't ready yet. Microsoft planned to spin portions of Cairo ideas, including indexing and Distributed Component Object Model, into NT 4, and save its directory features for NT 5, which ended up being named Windows 2000.

However, half a decade after its first announcement, there was nothing really new about "Cairo technologies."

In 1995, Steve Jobs had already demonstrated NeXT's Distributed OLE, the Windows port of its Portable Distributed Objects, two years before Microsoft planned to ship anything; NeXT had shipped its own PDO technology back in 1993.

Novell had also shipped its NDS directory server in 1993, seven years before Microsoft would get around to delivering ActiveDirectory in Windows 2000.

Many years after promising Cairo, Microsoft was still working on its long overdue vision of the future, while other companies had actually delivered it.

Most strikingly, it never released its Object File System, but kept bringing it up as the future; in 2001 it was added to the new plan for a next generation system: Longhorn.

Hasta la Vista

Cairo worked so well to suppress competition and distract from the quality of the products Microsoft actually shipped in the 90s, that Microsoft reused the same strategy in the next decade. Note the parallels:

Cairo:

-

•Announced in 1991 to distract from the lack of anything dramatically new in Windows 3.0.

-

•Expected in 1994. Pushed to late 1995, pushed to late 1996, intended to debut in 1997. Changed to a vision.

-

•Core features dropped. Ended up as polish on the existing Windows 3.0: Windows 95.

Longhorn:

-

•Announced in 2001 to distract from the lack of anything dramatically new in Windows XP.

-

•Expected in 2003. Pushed to 2004, 2005, pushed to late 2006, intended to debut in 2007.

-

•Core features dropped. Ends up as polish on the existing Windows XP: Windows Vista.

Fraud as a Business Plan

The magic of the Internet is helping to point out the tragic fallacy of believing in Microsoft's promises. Microsoft assures us that it won't ever slip half a decade between operating systems again, but what about the fact that that's all it has ever done?

Looking back, while it appears Microsoft has shipped regular products, in reality what it has shipped in the last two decades of Windows has been a series of apologetic stopgaps without ever being ready and able to ship what it actually promised to deliver.

Those placeholder products were far inferior to what competitors were offering. They were actually far inferior in many cases to products that predated them by many years.

In addition, the futuristic Cairo plans Microsoft failed to ship were actually delivered years ahead of schedule by other vendors. Why does Microsoft keep getting airtime? The company is a huge fraud, and has been for decades.

Pink vs. Cairo

Interestingly, while Apple's problems in delivering Pink and Copland between 1990-1995 are frequently cited by analysts, the world seems to have collectively forgotten that Microsoft's own equivalents, Cairo and NT, were similarly problematic, and that Microsoft pulled the same stunt again with five years of vaporous Longhorn plans.

In reality, Apple has shipped major developments that pushed the state of the art, even when they were not successful. It shipped its graphical Mac far in advance of Microsoft, despite the fact that both companies were talking about delivering graphical windowing systems in 1981.

Apple also delivered A/UX as its own commercial Unix, as well as operating system products that included ProDOS, SOS, GS/OS, and Newton. All were original products, not just outside work licensed to resell.

In the last five years, Apple has delivered far beyond anything it promised. Microsoft not only has far more failures under its belt, but more problematically, has used its market position to prevent, postpone, and kill technology offerings that were better.

Even worse, in the last five years, Microsoft not only hasn't delivered what it promised at all, but instead is pushing Vista as something the world should be excited about getting.

No, we shouldn't be excited, because it offers very little that is new and noteworthy, and entirely fails to match what it promised back in 2001.

What About BOB?

A number of industry wags have chimed in to "defend Vista" from any criticism. Among them is Mark Stephens, writing under the name Robert X Cringely. Recall that referenced "I, Cringely" before when talking about the absurdity of the Red Box Myth, and again when talking apart crazy rumors involving Apple and Amazon and their online movie stores.

His latest article is troubling because, as a historian of sorts for the tech world, Stephens seems to have forgotten so much of what really happened apart from Microsoft BOB, which he describes as "the so-called social interface operating system I always figured was really named after me."

That's a puzzling thing to say, because BOB wasn't an operating system, nor was it ever called "social," and Stephens' name really isn't BOB.

In reality, Microsoft BOB was a shell for DOS that tried to look somewhat like a 256-color PC adventure game. Instead of having windows on a desktop, there was a cartoon room with little cartoon characters. Users could leave one room to enter another, based on what they wanted to do, apparently. Most users just wanted out of the rooms entirely.

Microsoft dropped BOB, but retained the annoying characters as one of the foremost innovations it has bestowed upon society.

Microsoft dropped BOB, but retained the annoying characters as one of the foremost innovations it has bestowed upon society. Clippy the paperclip was added to Office as one of its assistants, and a little dog was added to Windows XP in its search field, apparently to distract users from the fact that Windows search doesn't work at all for actually finding files.

It does have an animated dog however, thanks to the legacy of BOB.

The real problem with BOB is that it didn't really matter. It keeps getting brought up as a scapegoat however, as it if were Microsoft's one problem from back when, and "hoo-boy, wasn't it a funny thing and what where they thinking?"

Noise about BOB entirely distracts from the fact that BOB wasn't Microsoft's one mistake, but rather characteristic of everything Microsoft has done since: a bad idea designed by committee and given a ridiculous interface that looks lame and insults the user.

So forget BOB, and stop pretending that anyone is really asking "will Microsoft be able to sell Vista?" Quite obviously it will, if for nothing other than the fact that it will ship on all new PCs. However, a number of other factors are working against Vista, which I examined in the series comparing Leopard and Vista. Those are the real issues.

Another real question is: will Microsoft get the chance to pull another Cairo-Longhorn stunt again? Will the world jump on Vista's lap and beg for another decade of waiting around for scraps from Microsoft's table that might come half a decade later, if they are lucky?

The real problem for Microsoft isn't today's Vista, but in maintaining interest for a proprietary operating system that is already plagued with legacy and architectural problems and faces the most credible competition the company has ever faced, both on the desktop from Mac OS X, and in the Enterprise with Linux.

Why This Won't Happen Again

Back in the days before web access, we got information on the tech industry several months late through magazines and newsletters. We didn't have access to sales reports on the week's market share of new products as they were released, so we had little basis for declaring the absolute failure of a product launch almost immediately. We had to wait months.

Conversely, companies also lacked information from consumers; they didn't get immediate feedback in the volume we have today. No individual had the ability to list problems and flaws and publish them widely; we had to wait for news to get out through those same old magazines.

That general ignorance, based on a lack of up to date information, was used to promote fictitious vaporware products that could choke to death real competitors. Vaporware vendors needed only to seed ideas about better products of the future to shift attention away from what was currently on sale by rivals.

Without any journalists exposing the tricks, the masses were easily manipulated to believe things that were not true at all. This technique wasn't invented for technology, it's as old as society. Control the news, and you can control the people. Revolutions have been commonly fueled by new sources of information that enlightened individuals and broke the secret mind control of totalitarian powers.

What Microsoft faces in 2007 is not going to be the lack of OEMs selling Vista for them, but the unraveling of its monopoly position and its ability to mislead the world again with promises of new, next generation technology just around the corner. We know better than that now.

Oh and Cringely, you can stop pretending the cat is still in the bag.

Next Article:

Platform Crisis: Robber Baron Piracy

This Series

Thursday, December 14, 2006

Bookmark on Del.icio.us

Bookmark on Del.icio.us Discuss on Reddit

Discuss on Reddit Critically review on NewsTrust

Critically review on NewsTrust Forward to Friends

Forward to Friends

Get RSS Feed

Get RSS Feed Download RSS Widget

Download RSS Widget