As Apple struggled with options for rebuilding or replacing its 80s Mac platform, and fended off competitive moves by NeXT and Be, Microsoft launched the third version of Windows, application environment for DOS. Here’s why Windows was able to rapidly spread as a new platform, and how it changed the computing landscape.

Platform Death Match introduced the difficulty of launching a new platform and the work involved in maintaining one. This series looks at the historical march of computing platforms, to sort out why winners won and why losers lost. While the computing environment is always changing, the same basic rules are in effect today, and will shape the future developments between Mac OS X Leopard and Windows Vista.

Previous articles:

1990-1995: The Rise of Windows

In the late 80's, Apple sued Microsoft over Windows 2.0, along with Digital Research's GEM/1 and HP's NewWave, in an attempt to stop look alike versions of the Mac desktop for the PC.

Digital Research, which had nearly copied the Mac desktop verbatim in GEM/1, agreed to make changes for their PC version, but the original GEM/1 was used unchanged on the Atari ST. Apple apparently saw little risk from Atari however, because it focused its legal attention on PC products.

Digital Research, which had nearly copied the Mac desktop verbatim in GEM/1, agreed to make changes for their PC version, but the original GEM/1 was used unchanged on the Atari ST. Apple apparently saw little risk from Atari however, because it focused its legal attention on PC products. Apple's lawsuits won some minor concessions, but were only a temporary setback. In reality, the lawsuits actually helped to entrench Microsoft's Windows.

Like an under-prescribed antibiotic, Apple’s legal action repressed competition to Windows, enabling Microsoft to advance as the only strong competitor left remaining.

The "look and feel" lawsuit failed to stop Microsoft Windows primarily because Apple CEO John Sculley had earlier licensed most of the key aspects of the Mac to Microsoft, under threat that Microsoft would otherwise withhold development of their Office software for the Mac.

Since Sculley had given away the Mac interface, and Apple hadn't ever patented the Mac environment, the court ruled that Apple didn't have a copyright case against Microsoft, but rather that the issue was simply a contractual dispute the two companies would have to sort out themselves.

Resolving the issue took nearly a decade; it wasn't completely closed until Jobs returned to Apple in 1997 and tied up the loose ends with Microsoft. In the meantime, the lingering issue left Apple and its supporters feeling complacent and ineffectually embittered about Windows, without Apple ever really taking any action to compete against Microsoft directly.

Apple Takes a Nap

Sculley's reign at Apple focused more on marketing than engineering; it transformed Apple from the dynamic and driven production company that Jobs had founded into a laidback experimental research laboratory more akin to Xerox PARC. Just like PARC, Apple began to play the role of a non-profit research and development think tank all the other tech companies would shake down for free ideas.

Rather than working to maintain its lead of the graphic desktop, in the early 90's Apple seemed content to doodle around with "advanced technology" and gained comfort in pointing out that it had already delivered what Microsoft was trying to build with Windows. That turned out to be a disastrous path for Apple, but the full consequences were hidden under a temporary illusion of ongoing success.

Apple had delivered A/UX, a Unix distribution with impressive support for the Mac system software; played around with porting System 7 to the PC; experimented with a new RISC workstation platform; begun work on a media architecture called QuickTime; developed the Newton handheld computer and a line of cameras, scanners and other peripherals; described a new messaging platform called PowerTalk; and incubated various other enabling technologies, but was having trouble creating any significantly marketable products beyond the Mac.

Notable platform lesson: Real artists ship!

A Rude Awakening

Apple's casual inaction met serious competition. By 1990, Microsoft's third version of their graphic shell for DOS had finally started catching on as a way to bring graphical computing to the large installed base of DOS PCs.

Suddenly the vast gulf between the graphical Mac and the text-based DOS PC narrowed to a critical point where the pent up demand for a low cost graphical computer could spark the gap. The high margin sales inflating Apple's high flying sails began to stagnate.

In addition to shipping its Windows 3.0 shell for DOS, Microsoft had also been working in a partnership with IBM since 1988 to deliver OS/2 3.0, also known as OS/2 NT.

The partnership intended to eventually replace DOS with OS/2, a modern operating system that could run new, native OS/2 software, as well as offering backwards compatibility with Windows and DOS applications.

However, as Microsoft began to see sales and adoption of its Windows 3.0 take off, it pulled away from IBM and eventually abandoned the OS/2 partnership. Microsoft instead changed its plans to "Windows NT," an effort to replace the DOS underpinnings of Windows 3.0 with an advanced, entirely new NT kernel owned by Microsoft.

The OS/2 platform, which had never gained serious traction, was now competing not only against the entrenched DOS, but also directly against Windows. Microsoft continued to talk about OS/2 as the future, calling it “Windows Plus,” while at the same time clearly shifting its resources toward developing its own NT operating system.

The Promise of NT

In order to deliver NT as an entirely new operating system, Microsoft assembled a design team of engineers lead by Dave Cutler, who was hired from DEC. Cutler had worked on DEC' VMS, which was the main OS contender against Unix in the higher end workstation market. NT's design reflects many conventions of VMS, although it also included many new ideas.

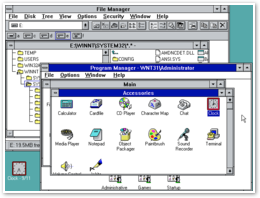

While intending to deliver Windows NT 3.1 in 1993 as the successor of the DOS based Windows 3.1, Microsoft found the performance of the new operating system wasn't going to be acceptable on most PCs.

Microsoft repositioned NT as a server and workstation product, and made plans to improve NT's performance so that it could eventually run acceptably on common PCs.

In the interim, Microsoft maintained both NT (NT 3.5, 3.51, 4, 2000) and DOS-based versions of Windows (3.11, 95, 98, 98SE, Me). Rather than pulling off a rapid transition from DOS to NT, Microsoft ended up struggling to converge the two systems over the next decade.

Microsoft envisioned NT as the everything platform. In addition to running existing 16-bit Windows 3.0 software, it was also intended to support subsystems able to run most DOS programs, new 32-bit Windows apps, OS/2 apps, and even POSIX software.

Each subsystem sat on top of an internal platform API, enabling NT to theoretically support any new API desired. Similarly, a hardware abstraction layer was designed to allow NT to support any type of underlying hardware. In addition to standard x86 PCs, Windows NT also originally ran on DEC Alpha and MIPS R4000 processors.

The Cruel Fate of OS/2

While NT planned support for different software, its focus was clearly on delivering a strong Windows platform, and really only paid lip service to OS/2 and POSIX. This allowed Microsoft to claim wide compatibility while really focusing developers’ efforts on its own platform. Microsoft also gave away Windows SDK developer tools to build support for the new platform.

After being abandoned with OS/2, IBM sought to provide similar compatibility, but went about it very differently. OS/2 intended to support DOS and Windows applications flawlessly, describing OS/2 as "a better DOS than DOS, and a better Windows than Windows." IBM spent significant efforts to provide seamless support for Windows 3.0 applications directly on the OS/2 desktop.

That strategy backfired. IBM's efforts to support Windows undermined any rationale for developing native OS/2 applications. At the same time, OS/2 couldn't provide perfect support for Windows applications, in particular support for VxD device drivers, so users really only saw OS/2 as "a lessor Windows than Windows."

OS/2's improved reliability and other unique features weren't enough to establish OS/2 as a desktop platform, and IBM's attempts to charge for the OS/2 SDK programming tools also helped repress native development for it, ensuring that OS/2 would never develop the critical mass of development needed to stand on its own merits.

While IBM struggled to keep OS/2 alive as a consumer product, its efforts were too little and too late. OS/2 ended up being widely used where reliability mattered, primarily in ATMs and telephone PBX and voicemail systems, but it was eventually abandoned by IBM as well.

Notable platform lessons: Backwards compatibility has to be a temporary bridge to a new platform, not a permanent crutch that preserves legacy or promotes competing platforms. Also: developers, developers, developers!

Flattering Apple

In developing NT, Microsoft borrowed more from Apple than just the look and feel of the Mac desktop. NT also borrowed a number of user centric, auto-configured engineering principles that made the new operating system more like the monolithic Macintosh than other existing systems, particularly Unix.

Microsoft also tried to bring the simplicity of the Mac desktop to server applications. Rather than expect users to configure sever settings by editing text files, as Unix sysadmins commonly did, Microsoft presented its file and printer sharing, remote access, and other services with point and click simplicity, and using buttons and icons similar to its Office applications which had premiered on the Mac.

In conjunction with NT, Microsoft also made a series of announcements of other plans. Under the code name Cairo, Microsoft planned to deliver extensive messaging services (resulting in Exchange Server), directory services (eventually delivered as Active Directory), and lots of talk about object-oriented things, clearly in reference to NeXT. Microsoft intended to match NeXT's advanced, object-oriented development frameworks, but never actually delivered on those ideas.

Death by Vapor

A big part of Microsoft's business plan has always involved pre-announcing broad plans to deliver products, in part to judge the reaction of the market. This strategy also has worked to kill off potential competitors, since the market tends to hold off purchases to see what Microsoft will deliver.

In the early 90's, an announcement of vaporware from Microsoft frequently amounted to instant death for the existing, competing products targeted. The company's more recent inability to deliver on its plans has resulted in its announcements carrying much less impact than they once did.

While Microsoft began to apply ideas pioneered by Apple in the server arena, Apple increasingly struggled to simply maintain the status quo. Those issues will be covered in the next installment:

This Series

| | Comment Preview

Read more about:

Read more about:

Send |

Send |

Subscribe |

Subscribe |

Del.icio.us |

Del.icio.us |

Digg |

Digg |

Furl |

Furl |

Reddit |

Reddit |

Technorati

Technorati

Click one of the links above to display related articles on this page.

1990-1995: The Rise of Windows NT & Fall of OS/2

Saturday, September 9, 2006

Ad