Can Apple Take Microsoft in the Battle for the Desktop?

Some analysts are nostalgic for the days when they could appear intelligent merely by gushing about everything from Microsoft. They felt safe in recommending everything the company released, knowing that there were no real alternatives, and that anything the company could deliver would more or less have to be purchased.

All their advice and analysis helped to create the general illusion that Microsoft was divinely fated to succeed, and that no rival could ever hope to challenge the company. That illusion helped to reinforce the real power wielded by Microsoft as the dominant vendor of PC desktop operating systems.

Maintaining that illusion was as important to Microsoft as a properly running propaganda machine is to a banana republic dictator. As power begins to falter, maintaining an illusion of strength becomes increasingly important.

Ironically, the desperate measures that are frequently taken to sustain such an illusion often serve to distract from the real problems that need to be fixed and subsequently cause greater damage.

The Ghost of Past Failures

Microsoft certainly isn't the first tech company to stumble in a grand way. Apple fell from its position as a leader in the tech industry in the 80s to being "hopelessly beleaguered" within a decade.

In Apple's case, the company began making serious mistakes during a decade of limited competition leading up to 1995. Once a real competitor appeared, Apple was not only also woefully unprepared for the challenge, but also stumbling in the delivery of its own plans.

Had Windows 95 never arrived, Apple would still have had plenty to worry about; its future plans were uncertain, its product strategies were unfocused, and its System 7 software had grown obsolete.

Apple had originally launched onto the scene as a new startup in the late 70s, and earned huge profits from selling the Apple II line.

After reinvesting those profits into developing the Macintosh, the Apple of 1985 was situated with the still very profitable Apple II business, and the prospect of developing a huge new market with the then groundbreaking Mac. How could it all slip away within ten years?

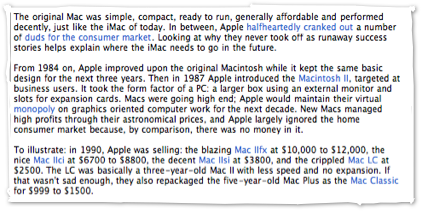

High Prices, Low Product Innovation

Instead of working to develop and popularize the Mac as a consumer product with broad appeal, Apple's CEO John Sculley artificially raised its price by $500, pushing it out of the range that many could easily afford.

The original Mac was already a relatively expensive product, because it required more RAM and other specialized hardware in order to deliver its entirely graphical environment. However, Sculley also packed the expense of a huge advertising campaign into the new Mac's price, bumping it from $1995 to $2495.

The original Mac was already a relatively expensive product, because it required more RAM and other specialized hardware in order to deliver its entirely graphical environment. However, Sculley also packed the expense of a huge advertising campaign into the new Mac's price, bumping it from $1995 to $2495.Between 1985-1990, Apple continued to release Mac models priced significantly higher than most consumers could afford, and positioned the company's Apple II computers as its entry level machines. Apple continued to sell the Apple IIGS, which was not compatible with the Mac, up to the end of 1992.

Jean Louise Gassée, Sculley's replacement for Steve Jobs, ran the Mac platform into the ground by insisting on high price points for new models, following the logic that Apple needed to get the most money it could out of the Mac’s technology.

His refusal to license the Mac interface, along with a demand to keep prices high on existing products without really pushing the state of the art, resulted in Macs being relegated to high end, professional niches.

His refusal to license the Mac interface, along with a demand to keep prices high on existing products without really pushing the state of the art, resulted in Macs being relegated to high end, professional niches. By Gassée's departure in 1990, Apple's only affordable Mac was a recycled version of a five year old machine.

Imagine Apple trying to resell the 2002 PowerBook G4 and Quicksilver Power Mac G4 as its low end laptop and desktop models today.

Many Apples, One Microsoft

The expensive, exclusive character of Apple under Sculley-Gassée, followed by rudderless drifting under CEO Michael Spindler, resulted in a company that was in fantastically bad shape by the time CEO Gil Amelio was handed the reigns. Amelio had turned around failures before, but Apple really needed more than a hatchet man to layoff a bunch of employees and cash out afterward with a huge paycheck.

Apple needed a consistent direction and a pilot interested in getting there. When Steve Jobs took over as CEO, Apple gained that sense of purposeful direction. Jobs cut everything that didn't point in the direction the company needed to go. Apple could no longer afford to spend huge fortunes running futuristic experiments in raw technologies that were not product related.

After a long, product-focused recovery between 1997-2002, Apple was once again in a position to start doing interesting things. The speed of development and new product introductions since then has exceeded anything in the company's past.

In fact, it’s difficult to identify any tech company that has been consistently able to debut as many successful new products as Apple has since 2002.

Many Apples, One Microsoft

In the decade between 1986-1996, Apple had three very different CEOs that presided over its descent into failure; each could at least partially blame the former for portions of the company's mounting problems.

In contrast, there has been one CEO of Microsoft since 1984: Steve Ballmer. Along with Chairman Bill Gates, Ballmer has always set the course for the company, giving Microsoft a singular personality in contrast to the turbulent changes during Apple's middle decade.

In contrast, there has been one CEO of Microsoft since 1984: Steve Ballmer. Along with Chairman Bill Gates, Ballmer has always set the course for the company, giving Microsoft a singular personality in contrast to the turbulent changes during Apple's middle decade. That means Ballmer really has nobody to blame for the problems Microsoft is now experiencing. Some of those problems are very much like Sculley's Apple under the direction of Gassée: a reliance on high prices and low product innovation to stretch the company's existing, threadbare assets while arrogantly ignoring the competition.

Competition Makes Companies Stronger

Just like Apple in 1990, Microsoft appeared untouchable in 2000. In reality however, both companies had really been softened by the lack of strong competition, and were so intoxicated by the praise of market analysts that they ignored brewing threats that were soon to develop into formidable rivals.

In 1990, Apple's competitors--including Atari, Amiga, and NeXT--were delivering specialized hardware DSPs and advanced operating system features well in advance of the Mac, but Apple felt secure than none of these companies could provide any significant competition.

Apple also didn't count on Microsoft offering much of a threat, since the company's Windows product had been an embarrassing joke until 1990, and was still laughably behind.

Apple wasn't prepared for Microsoft's Windows 95, followed by its four paid updates that were released over the next five years. That lack of preparedness, exacerbated by poor governance, lead to major troubles for Apple within just a few years.

The analysts that had previously celebrated the company were quick to turn on it, and discount every effort the company made to recover. Increasingly, analysts compared Apple to Microsoft--a very different company with an entirely different business plan.

The Turning of Tables

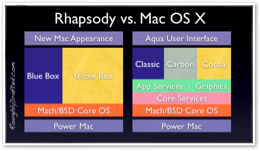

In 2000, Microsoft Windows was still a poor product, but it had replaced DOS on hundreds of millions of PCs, and was strong competition to the ten year old operating system that Apple was still trying to sell.

When Windows 2000 shipped, Apple's efforts to sell Mac OS 9 and its delayed attempts to deliver Mac OS X similarly appeared laughably behind the times.

When Windows 2000 shipped, Apple's efforts to sell Mac OS 9 and its delayed attempts to deliver Mac OS X similarly appeared laughably behind the times.It was Microsoft that wasn't ready when Mac OS X Jaguar was delivered in 2002; it offered many of the key features intended for Microsoft's Longhorn, expected in 2003.

Apple then rapidly delivered Panther in 2003, Tiger in 2005, and then moved Tiger to Intel in 2006. Meanwhile, Longhorn hadn't gone anywhere but back to the drawing board.

Now that Windows Vista has finally shipped, critics are panning it as being an overpriced, unnecessary upgrade. Customers who have been waiting for Vista to ship have taken the opportunity to investigate the Mac, which not only offers a better product now than Vista, but also promises a further leap beyond Vista later this year with the release of Mac OS X Leopard.

This All Happened Before

Ballmer's incredulous confusion as to why Vista upgrades are not taking off sounds eerily similar to how Apple's executives refused to acknowledge the threat of Windows 95 as Mac sales slowed.

Ballmer has repeatedly dismissed Apple as a competitor, recently stating, “Remember, when you're the little tiny niche guy who owns about 2 percent of the worldwide market, you can be cute one time and it helps you grow.”

That was his brilliant response when asked by BusinessWeek about Apple’s high profile ad campaign calling attention to the security and reliability problems in Windows in comparison to the Mac.

Back in the mid 90s, it was Ballmer’s Windows 95 getting all the attention, while Apple’s Copland and Taligent projects fell apart. Apple revealed that it really had no alternative plans and started looking.

After finally delivering the disappointing Vista--which is regularly compared to Apple’s two year old Mac OS X Tiger--Microsoft has yet to admit any mistep. Instead, it talks about nebulous plans for the next version of Windows, which might be delivered in a few years.

Microsoft avoids direct comparisons with Apple and pretends there is no competition it needs to answer.

A Painful Vistula

Many of the pillars promised for Longhorn were stripped from Vista in order to have something to ship four years after it was originally promised. Even so, reviewers have described Vista as “beta quality” and recommend waiting on Vista until Microsoft ships its first service pack.

Many companies have put off buying Vista entirely. The US Federal Department of Transportation has put an indefinite moratorium on purchases of both Windows Vista and Office 2007, stating in a memo:

"...there appears to be no compelling technical or business case for upgrading to these new Microsoft software products. Furthermore, there appears to be specific reasons not to upgrade."

As PC sales continue through the year, Microsoft will be able to claim that an increasing number of users are "buying Vista," which ships with new PCs. However, many businesses are buying new PCs and installing their own software images, commonly Windows 2000. Some have only recently moved to the six year old Windows XP.

When Apple reports additional sales of Macs, it actually means more active users of the latest Mac OS X.

How the Battle for the Desktop is Changing

The real battle for the desktop isn't between Mac OS X and Vista, but rather between Apple's Mac and the Windows-based products offered by PC hardware makers.

Apple is competing against Microsoft's offerings, but it's not a retail software battle. Apple is using its integrated software to eat up the prime portions of the PC hardware market.

As PC makers fight to offer the cheapest boxes online and in big box retail stores, Apple is expanding its share of the market by building its own, smaller retail stores where users get a better buying experience and better support. Apple is also targeting products to what consumers want, not just producing what is easy to build.

A Better Product Mix

Windows enthusiasts like to recount Apple's long static 2% share of the worldwide market for all computer systems. However, Apple is no Dell or HP. Apple sells systems targeted at profitable portions of the PC market:

-

•higher end Mac Pro workstations and Mac Book Pro laptops for creative professionals

-

•complete, simple iMac, MacBook and Mac mini systems for consumers

-

•entry and mid level workgroup servers and RAID units

Conspicuously missing from that lineup is anything like the volume loss leader PCs sold by HP, Dell, and no-name PC makers: the $600 systems that are stripped down to include just the core components needed to run Windows.

Conspicuously missing from that lineup is anything like the volume loss leader PCs sold by HP, Dell, and no-name PC makers: the $600 systems that are stripped down to include just the core components needed to run Windows. Those boxes offer scant profits, so they come with minimal support and are packed with adware and vendor junk that attempts to sign up users for additional security, anti-virus, and other services.

There is little interesting innovation going into cheap PCs, and the result is a product that is destined to disappoint. That helps to explain why the desktop segment of the PC market is sagging.

The Death of the PC

Consumers are increasingly interested in laptops, where differences in quality are more obvious.

"In the U.S. market, the focus continues to be on the transition from desktops to notebooks, with notebook growth being the sole bright spot while desktop shipments continued to decline.” - Bob O’Donnell, IDC, Oct 2006.

It's easier to see the vast difference an extra $400 makes for a new laptop purchase than with a basic PC that might end up shoved under a desk. That's why Mac Books are eating into rival laptop sales and the already stagnating market for basic PCs.

Consumers are willing to pay more for better laptop hardware because of its perceived value and potential for resale. Vista is non-returnable, non-transferable, and has zero resale value. It should be no surprise that there is little consumer demand for paying hundreds of dollars for such a software upgrade.

That’s forcing Microsoft to push more activation restrictions in Windows Vista, killing the same pirate market that has helped prop up the Windows monopoly. While Microsoft struggles to force its user base to pay for a half-baked upgrade, Apple is finding lots of new customers willing to pay for premium hardware.

The Cream of the Market

Microsoft makes no premium from sales of higher quality PC hardware; it supports HP and Dell in their crusade to profit from selling more units of e-waste more often.

Overall market share numbers capture the vast scale of PC disposability, but do not reflect the product profitability that comes from building a better quality product.

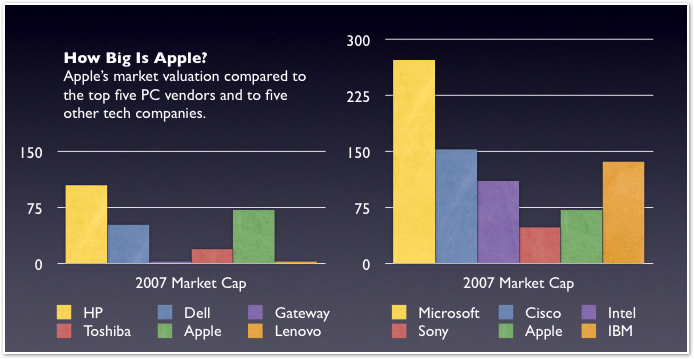

While Apple is cited by Gartner and IDC as selling around 5% of all the computers in the US, it isn't obvious that Apple's 5% share is the cream of the market; it’s actually worth more than the same or larger percentage shares held by rivals.

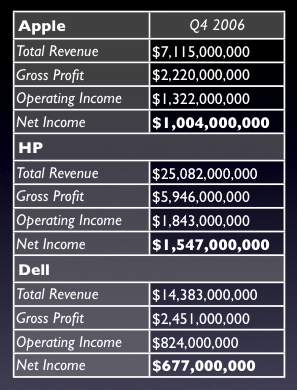

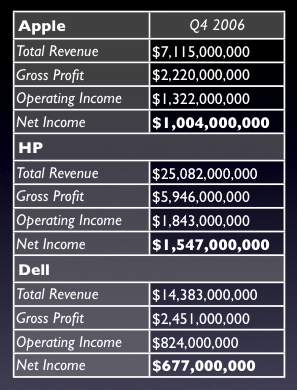

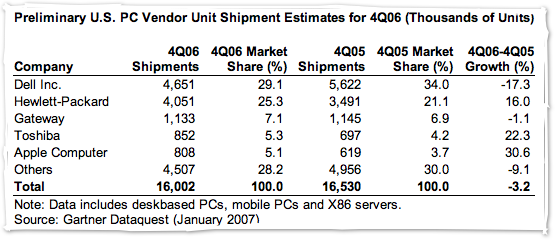

There were 9.8 million Macs sold in the last two years, up from 6.2 million in the previous two year period. Those numbers don't compare with the stunning volume of PCs shipped by HP and Dell--which each sold 38 million PCs in 2006 alone--but Apple's profits do.

In the forth quarter of last year, HP and Dell combined sold 10 times as many PCs as Apple in the US, earned 5.5 times as much revenue as Apple, but together only ended up with 2.2 times as much net income as Apple.

In other words, Apple earned nearly half as much net income with its 5% share the market as HP and Dell together, with their combined 55% share of the US PC market: $1 billion for Apple vs $2.2 billion for HP and Dell together!

Adding in third place PC maker Gateway makes things look even better for Apple, because Gateway actually lost money all year, despite shipping more PCs than Apple and capturing a larger percentage of market share.

A large chunk of Apple's profitability comes from the iPod and other consumer electronics. Those sales are increasingly directing consumers to the Mac, and will help float the company through downturns in PC sales.

Consumer electronics is also a market segment that Apple’s PC competitors beholden to Microsoft can't enter. Dell struck out with its PlaysForSure DJ music players, and HP has similarly stumbled in trying to sell PDAs running Microsoft's WinCE based Pocket PC.

Being independent from Microsoft actually helps Apple tremendously; the rest of the industry’s reliance on Microsoft hamstrings them from effectively competing with Apple.

Fewer Windows = Better View

Microsoft has never cared about which vendors were selling PCs, because all of them had to buy Windows licenses. However, as Apple takes away PC sales, an increasing smaller number of Windows licenses are sold.

Since Macs have a longer usable life span, every new Mac sold means a smaller future demand for cheap replacement PCs running Windows.

More Macs sold to consumers also means less demand for Microsoft-only solutions in general, such as websites that only work correctly in the Internet Explorer web browser.

Banks, retailers, and other businesses with IE-only web sites not only lose access to 5% of their users, but 5% of their best customers.

The End of a Monopoly

Combined with the dominance of the iPod over devices using Microsoft's PlaysForSure, the imminent goring of Windows Mobile by the iPhone, and the shift of support across the industry from Windows to Linux in servers, the days of Microsoft's monopolistic grip on the desktop are winding down.

Apple doesn't have to take a majority share of the desktop market to win, it only needs to take the most valuable segments of the market.

Once that happens, Microsoft will be forced to choose whether it wants to battle Mac OS X for control of the slick consumer desktop, or repurpose Windows as a cheaper, mass market alternative to Linux in corporate sales.

If it doesn’t make a choice, the company will face difficult battles on two fronts. Microsoft hasn't needed to compete for years, because had been able to use its monopoly position to prevent competition. Those days are now over.

Microsoft is not exactly in great shape to be competing against smarter, nimbler, and less expensive rivals.

Is Apple big enough?

One remaining bit of illusion is that Apple simply can't compare to the heavyweights that control the industry because of its "small market share." A comparison of Apple's market capitalization--the value of the company assigned by investors in the market--helps to explain why Apple can't be ignored.

Like reading RoughlyDrafted? Share articles with your friends, link from your blog, and subscribe to my podcast!

Did I miss any details?

Next Articles:

This Series

|

|

|

|

Del.icio.us |

Del.icio.us |

Technorati |

About RDM |

Forum : Feed |

Technorati |

About RDM |

Forum : Feed |

Sunday, March 4, 2007

Send Link

Send Link Reddit

Reddit Slashdot

Slashdot NewsTrust

NewsTrust