Why Apple Failed

Apple's recent quarterly earnings report blew past all expectations. More importantly, dramatic unit sales growth shows the company is executing a working strategy for building the Mac platform. That raises the obvious question: why has Apple's market share historically been so low, and why did Apple fail to make any progress in the 1990's?

Here's a look at why Apple's platform fell into crisis, and why the solutions proscribed by analysts didn't work. A follow up article will describe how Apple turned its fortunes around, and why the company is now poised make further gains.

The Market Share of Apples and Oranges

Analysts have long been fixated with Apple's market share. However, limited market share wasn't Apple's real problem. That's why attempts to "fix" Apple's market share--by following strategies which worked in the PC world--didn't work for Apple.

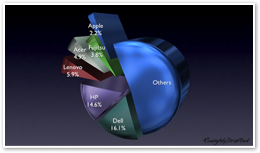

Market analysts commonly report individual PC manufacturers' unit sales and their market share, or percentage of the overall market. This is useful in determining how well a vendor performed relative to its own previous sales and in comparison to the rest of the market.

Market share numbers are meaningful for companies that directly compete for the same sales. Comparing Dell and HP is equivalent to comparing Ford to GM; in both cases, the two sell a similar range of models in similar price categories.

However, overall market share numbers convey less useful information when comparing specialized companies with an entirely different product mix. Comparing Apple's worldwide market share to HP or Dell fails to consider that Apple sells a different product mix to a very different segment of the market.

Imagine comparing the market share numbers of BMW against Ford and GM; BMW sells motorcycles and luxury cars, and does not sell pickup trucks or economy cars, nor do it sell large fleets of cars to rental agencies.

Overall market share numbers have always been particularly unimpressive for Apple, because the company similarly has never participated in large segments of the PC market. Apple has never had significant corporate PC sales, nor does the company sell volume, loss leader PCs at disposable prices.

Apple sells premium computers with a unique operating system. This leaves it with no direct equivalent in the market. Apple's very different product mix means that market share not only doesn't tell the whole story, but actually was not the real problem.

In fact, all the focus on driving up market share turned out to be a red herring, and spawned disastrous business decisions that made Apple’s actual problem worse.

Apple's Premium PCs

Of course, almost all other PC manufacturers also sell premium PCs, and in fact, this is where they earn most of their profits. The two largest PC makers, Dell and HP, will gladly sell consumers machines from their premium lines, but are also forced to service the shallow profits of broad waters in low-end PC market.

These manufacturers typically use advertisements of $299 eWaste PCs to lead consumers toward their higher end models. If Dell gave up its sub-$500 PC sales, it would not lose profit initially.

However, HP and others would happily rush in to accommodate those entry-level PC buyers, and similarly seek to point them toward more expensive machines. Dell would eventually lose important sales that resulted from the profitless low-end.

Low-end PC sales are a high volume, low profit business, but a critical segment of the Windows PC market. By keeping sales volumes high, Dell and HP can lower overall manufacturing costs by benefiting from large economies of scale. They are also very much aware that every PC they fail to sell will be sold by a competitor, because demand in the PC market is huge.

The Mac Platform Problem

Apple serves a specialized market that has always been constrained to a limited audience of potential Mac buyers. Macs and PCs haven't been interchangeable, so a company buying a new fleet of computers couldn't even consider Apple's products.

Comparing Apple's Macs with the market for various manufacturers' PCs is very much an Apples to oranges comparison. Macs weren't ever part of the overall PC market, because they weren't PCs at all. They couldn't run DOS or Windows, which was the definition of PC ever since IBM applied the letters to its first home computer.

Industry analysts liked to talk about Apple's market share, but the company's real problem wasn't its share of the overall PC market, but rather the size of its own limited market.

If Apple could create and maintain a functional Mac market, its share of the overall market for PCs wouldn't matter any more that its share of the market for all devices that used electricity.

Apple didn't need PC market share, it needed Mac market expansion. Those two ideas may sound like the same thing, but they are achieved in very different ways.

Unlike the various PC vendors, the only way Apple can sell more Macs is to entice new users to its unique platform. As the Rise and Fall of Platforms has outlined, moving established users to a new platform is very difficult.

For HP, Dell, and all the other PC makers, stealing each other's PC sales is much easier. They can simply lower prices, increase performance, or target sales in different channels. For example, Dell pushed to the top of PC sales by building an efficient, direct mail order operation.

Thinking that Apple could simply follow the success stories within the PC world, analysts determined that Apple needed to be more like HP and Dell, or alternatively more like Microsoft.

They were disastrously wrong, primarily because Apple wasn't selling the same product as either the PC makers or Microsoft. Simply copying their successes wouldn't work.

Apple struggled to expand the Mac market in 1992 by broadening out into new retail outlets, including Sears, with a new, low-end Performa line. This effort to sell Macs more like HP failed due to poor marketing and poor retail presentation.

Additionally, the low profit margins on low-end computers meant that PCs with cheaper components were more profitable for retailers than Macs. Few retailers wanted to invest in selling Apple's unique platform for the company, and none were interested if it meant lower retail profits.

If Apple wanted to sell more Macs, it would have to learn how to do that itself. That didn't happen until 2001, when Apple opened its first retail stores.

Interestingly, while Apple failed to sell Macs like PCs, it later has succeeded in selling Macs where PCs failed. Sony and Gateway's retail stores didn't work, but were the right fit for Apple. The reason: Apple's Mac and PCs represented very different products.

Being like Microsoft: Disasters with Clones

In 1995, Apple began experimenting with Mac clones. It licensed hardware designs and Mac OS 7 software to Motorola, Power Computing, and several other hardware manufacturers, with the intention that they would expand the market for Macs, particularly into the growing low-end of consumer PCs.

This was supposed to make Apple more like Microsoft, earning its profits from hardware reference designs and licensed software. However, the assumption that Microsoft's business plan would be easy to copy was wrong.

As pointed out in the Microsoft Invincibility Myth, even Microsoft has found it impossibly difficult to duplicate its success with Windows into new areas, from WinCE, to handheld Windows PCs, to WMA music players.

In fact, Microsoft has recently abandoned new efforts in software licensing to begin copying Apple's model with the Macintosh: both the Xbox and the Zune involve integrated hardware and software sold directly by Microsoft; there are no licensees.

Similarly, video game consoles from Sony and Nintendo have always followed this model, and there are few other examples of successful companies who only license technology designs for others to build, particularly in the consumer electronics market.

Being like Dell: Disasters in Direct Sales

Additionally, cloning also attempted to sell Mac hardware more like Dell: target the large low-end market with cheap hardware and trade lower profits for higher volumes using a direct sales model.

The president and CEO of Power Computing, Apple's leading cloner, was originally from Dell, and the cloner ran a direct sales operation similar to Dell's.

It turned out that the analysts were wrong. Cloning didn't work for Apple for the same reasons that Apple was having its initial problems: the company had a limited potential share of the market. Copying the business model of commodity PC makers was not going to work for Apple because the company didn't have the same market or demand volume to exploit.

Instead of expanding the overall Mac market, cloners simply siphoned off the cream of Apple's sales. The smaller cloners were able to offer low volume, faster chips first, enabling them to take the high margin sales away from Apple. That was the exact opposite of what Apple's executives had imagined would happen.

Just as with its retail initiatives, Mac clone licensing and the low-end, high volume sales models that worked for PCs didn't work for Apple. Even more importantly, these efforts to copy PC makers failed to attack the real problem: Apple was doing little to entice new users to the Mac platform.

Cheaper Macs were not increasing market share, they only served to move existing Mac users onto lower quality machines. Apple really needed to give new consumers a reason to buy a Mac. If Apple could expand the Mac market, it wouldn't need to worry about market share.

No Reason to Buy Macs

Prior to Windows, Macs held an obvious advantage in running desktop publishing and graphic design applications. As Windows began to develop into a comparable product, Apple fell behind in progressive development of differentiating features.

Once a leader in multimedia with the innovative QuickTime, Apple fell into a distant third place behind Microsoft and Real in the highly visible Internet media streaming market.

Apple also failed to deliver the new System 8, code named Copland. Those failures also impaired third party development.

The Mac was dying was because nobody had any reason to buy it. Without offering a compelling reason to buy a Mac, low prices, retail exposure, and profit sharing with cloners did nothing but make the situation worse.

The NeXT Plan

After buying NeXT in the final days of 1996, Apple spent several years investing in its new, NeXT based operating system. However, Mac OS X in itself was not going to sell a lot of new Macs. Apple still needed functional reasons for users to buy Macs: competitive software applications that would serve as killer apps, just as PageMaker had a decade earlier.

During the development of Mac OS X, Apple's fortunes rested largely upon Microsoft's Office suit of business applications, print production and graphic design software from Adobe and Quark, and Macromedia's suite of web design tools.

These four companies forced Apple to delay its migration to NeXT in order to support the classic Mac OS. Without the assurance that Apple would even survive the decade, they did not want to invest in an entirely new Mac platform.

Apple's existing Mac platform was almost entirely dependent upon these four developers; without them, Apple's Mac would turn into another Amiga or Be: interesting, oddball hardware which lacked much serious software.

Apple was forced to dump its initial plans to quickly migrate Mac users to NeXTSTEP under the code name Rhapsody, and instead undertook an extensive engineering effort to completely reengineer a new hybrid operating system and development environment.

During the development of Mac OS X, Apple polished the existing classic Mac OS, and salvaged what it could of Copland developments. Apple modernized its existing Mac APIs into Carbon, which would run software in Mac OS 9, and later allow it to run natively in Mac OS X.

Despite fixing the obvious flaws in Apple's operating system offering, Mac OS X did not in itself solve Apple's problem. The company now only had an improved platform that nobody had any reason to buy.

The real solution to Apple's problem was stumbled onto by a fortunate accident.

This Series

Sunday, October 22, 2006

Bookmark on Del.icio.us

Bookmark on Del.icio.us Discuss on Reddit

Discuss on Reddit Critically review on NewsTrust

Critically review on NewsTrust Forward to Friends

Forward to Friends

Get RSS Feed

Get RSS Feed Download RSS Widget

Download RSS Widget